About the Author and Illustrator

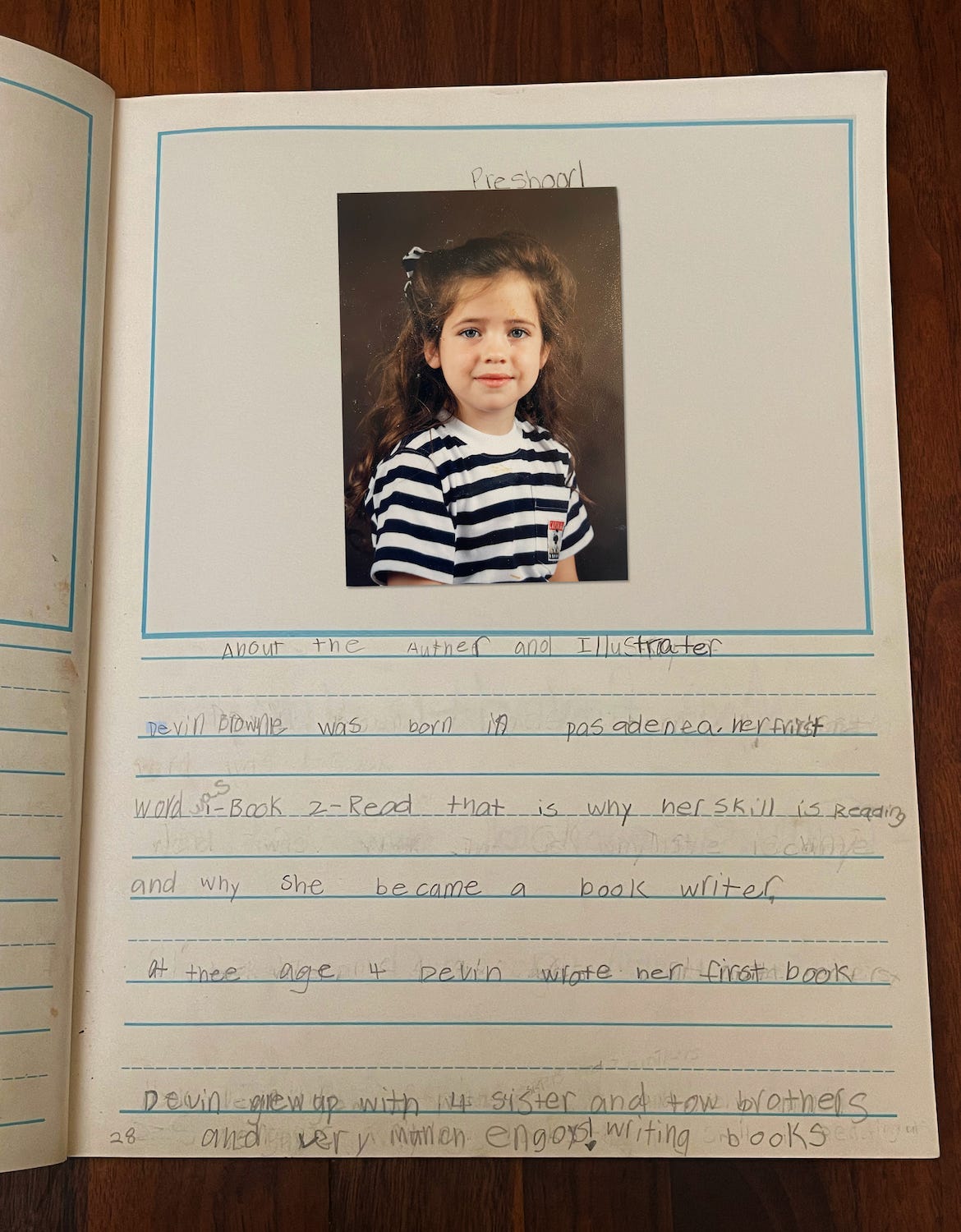

I’ve been trying to decide if starting a Substack means I’m an abysmal failure who has in every way let down this sweaty little girl in stripes, or if she’d approve and maybe even be pleased. When I was small, all I wanted to do was write books, mostly books like Roald Dahl’s, although it was tricky, because I wanted to be him, but I also wanted to be Matilda. By this measure, little me would likely be disappointed, if not confused by the trajectory of writing a first book at thee age of four and then writing a first… Substack post at the age of 40. But I was only singularly obsessed with books because that’s all I knew. My mom owned a children’s book and toy shop she ran out of a room by the garage and its inventory was always overflowing into our house, filling some rooms so completely there was only a pathway to get through them. So I don’t think I ever thought, as a kid, about “where” I would write and I’m fairly certain it would have surprised little me to learn that when a grown-up says she’s a writer, the surest form of reply is: for whom? It never would have occurred to me that I would write for anyone else.

Perhaps on some level, I knew I just wanted to write for myself, though I spent the better part of two decades trying to do otherwise. I did this for all the usual reasons: money, ego, external validation, and, at least in the beginning, a genuine desire to be a part of publications I looked up to and loved. (By this point, I no longer wanted to write books like Roald Dahl, but longform journalism like Joan Didion.) I can’t tell you exactly when I finally stopped trying to make it as a freelance reporter (had my career collapsed or had journalism as an industry collapsed or both?), but the signs it would not go well were there from the beginning. I remember winning an award in college for an essay I’d written, and afterwards going to see the professor, himself a beautiful writer, who’d helped me with it to thank him. He congratulated me and gave me a hug, but then he said something strange and jarring and that seemed to me to be totally at odds with what had just happened. Enjoy this moment, he told me, there probably won’t be that many more like it. He’s turned out to be right of course, but at the time, I somehow didn’t think his advice applied to me. It’s hard to imagine when you’re so good at school that you’ll also be so bad at life.

And I was—or rather I was bad at building a career as a writer, at doing the kinds of things writers need to do to get published by big publications, or, even more mysteriously, get hired by one of them. After college, I was an intern at an alternative weekly in L.A., and an editor there generously assigned me a story about student protests in South Gate (in an email titled “Slouching Towards South Gate,” no less, upping the stakes). I say generously because I was, at that age, something of a train wreck professionally—I couldn’t get anywhere on time, couldn’t finish anything on time, and the rules of the workplace so completely eluded me that I still signed my emails to him “xo.” Somehow I still got to report the story and one other, which were both to be in a special issue about the state of activism in Los Angeles, in 2005. I was elated I was going to be published in this weekly (really, published at all) and I told everyone I knew and then went every week to pick up the new issue, searching the table of contents for my byline (I was going to have a byline!), until I finally realized, I can’t remember how, that the entire issue had been canceled. For months, every time I saw one of my siblings or friends I’d told I was going to be published, I felt terribly embarrassed, as if I’d made the whole thing up, even though I hadn’t.

I now know this kind of thing happens all the time, and the more efficient response would have been to just keep pitching, and right away. A year or so later, I went out with a guy who was then a young columnist at the L.A. Times and he was horrified at how I’d handled this and other freelance opportunities that had sputtered and died. Once the door is open even a little, he told me, you knock and knock until it’s all the way open—that is how writers get regular assignments or bigger, more interesting assignments. This is true and I did eventually pitch to this particular weekly again, and got stories in it twice, and other news outlets several times. But then came the next, bigger problem which is what happened when the pieces were published.

I was not, especially in the beginning, writing about public corruption or issues of national security or anything of real consequence. But it didn’t matter—I cared so much about the stories I was writing and the people I was writing about, even the ones I did not particularly like, or the ones who had politics I really did not like. They had given me their time and let me into their world when I had basically no byline, no following, and no affiliation with a news organization beyond the term “freelance” which, in my experience, was always a tenuous relationship at best. I felt like such a nobody, I was honestly honored anytime anyone was willing to talk to me about anything. And if they did, I thought I owed them all the time they asked of me back. I remember requesting an interview with a man named Ron, a real talker, who worked for the Audubon of Kansas. He agreed, and then copied me on every single email he sent in the summer of 2009 about the black-footed ferret reintroduction program in Logan County, Kansas. Even though I wanted to talk to him for a piece about prairie dogs, I felt it only fair that I read every single one.

I knew I had no real skills and nothing to offer the world except this: I could show interest in people who generally didn’t garner much interest, and write about them in a way where they felt understood, represented fairly, that they had been put into the public record properly. I was not out to embarrass anyone. I did not want to betray anyone. And although it took being on the receiving end of a few irate emails, I learned I did not want to surprise anyone either. On the contrary, I wanted to get it right not only for their sake, but also for mine: I usually felt like an idiot while visiting their world, as any outsider or neophyte would, and I was anxious to prove in the piece that I was not.

And so when the articles came back from edit, or worse, when I saw them in print and they read like they had been written by a television reporter from 1987, I usually cringed. I almost always sent the people I interviewed emails, apologizing for a sensational headline or the oversimplification of an issue or the out-of-touch tone, which I tended to take especially hard because I thought at least part of a reporter’s merit came from being current and knowing what’s happening now. It was never what I meant, and when you are someone who is trying do this and only this with your life and believe you can’t do anything else, it can make you very sad.

Now, I suffer no delusion that the drafts I turned in were great or even good. They needed an edit and I needed an editor. When I started my first full-time reporting job, I was so unaware of how the world worked, I remember reading a press release at my desk and wondering aloud, what does AG stand for? And my editor, standing nearby, had to tell me. From him and other editors at that job, I learned how to submit a public records request, how to break a story, and that I should change “Dad” to “Peter” in my phone to thwart any potential kidnappers in Mexico who might search my phone looking for my parents to call and demand ransom. These editors were mostly middle-aged men at a public radio station in Arizona, so perhaps not the most cutting edge, but they believed, as I did, that an informed electorate was essential to a functioning democracy, and they often provided much-needed context to my reporting, helping me see whatever I was covering as a part of a larger historical pattern I was too young to know anything about. On how to report a story, we rarely disagreed. It was in how to tell the story that there were problems.

I have mentioned several of these issues above, but there was a problem in many ways even bigger and more fundamental and it was there from the start. During the interview for the job in Arizona, the managing editor looked down at the work samples I’d submitted as part of my application—a profile of a tamalero scored to a song by the Orishas and a series of highly-stylized and highly-designed stories I’d written while living in the entryway of a Spanish-speaking family’s apartment in Los Angeles—and then asked me, suspiciously, “Are you a journalist or an artist?!”

So this was it: you could either be a journalist or you could be an artist, but you could not be both. It really couldn’t have been any clearer, but I was determined to get the job, so I ignored the implications of how he’d framed this question and then spent years feeling somehow surprised and frustrated when he and other editors said no to pretty much any original pitch. How I ever thought they’d say yes to some of these, I’m not sure. Can we embed on both sides of the border, with the people who are trying to catch and the people trying not to get caught, like The Wire? Can I write a piece where the main characters get to speak at such length they get their own mini chapters, titled like the ones in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao? And can those mini chapters be framed with the kinds of beautiful borders popular in Spanish-language newspapers at the turn of the last century? I never talked at length with all the editors about why they said no, but my sense was they felt anything that was too creative or artistic or entertaining undermined the seriousness of the reporting, and thus the seriousness of their news organization.

Anyone paying even the slightest bit of attention can see the news media, as an industry, is struggling, if not on the verge of total collapse. But I don’t think any reasonable person can argue this is because newsrooms have been too creative. With very few exceptions, they have not been—not in their storytelling, and certainly not in their revenue model. I think it’s imperative that we change this. Why? Because we live in a world in which most people consume news for affirmation, not information. It is enormously comforting to do so, and the algorithms that deliver us our news know as much. There is, as far as I can tell, only one way to interrupt this and that is to tell stories with emotion, narrative, surprise, beauty—art. Facts alone are not enough.

This is why I’m starting The Portland Stack. Here, I’ll be telling stories at the intersection of journalism and art, mostly about housing, houselessness, public safety, and the social contract, but also about other things, relevant to readers not only in Portland, but all along the West Coast. (And maybe elsewhere too?)

As of right now, I’m planning on 2-3 posts per month:

week one—a longform, deeply reported story done in collaboration with an artist (for examples, see this, done in collaboration with the incredibly talented Emily C. Martinez and/or this, made with my favorite animator)

week two (coming soon)—a Q & A with someone who has insightful, interesting things to say about the issues central to The Portland Stack

week three—varies: either a short, curated list of articles, essays, podcasts, books and/or places and projects in Portland I especially like & want to recommend or a personal piece like this one or an update on how it’s going as a writer/entrepreneur on Substack

It’s tremendously exciting to write this and think about what’s to come. I’m going to get to write the stories I think are most important, without having to convince anyone they’re important before I begin, in the way I think serves the story best. And the stories will have pictures! Truly, I’m living the life of my little self’s dreams. I’ve only just realized, in getting to the end of this piece, that it’s not actually her I’ve had to worry so much about letting down. The disappointment, if any, is coming from another littler self—the one who so badly wanted to get in the Weekly and publish Slouching Towards South Gate in a place everyone would see. Traditional journalism did break her heart a little. But the other versions of myself, current one included, think I’m really going to engoy this Substack and I hope you do too.⬥