What Measure 110 could have looked like

We needed this pilot program between police officers and peer support specialists from the start.

By now, even the casual news reader must know that Measure 110, which decriminalized possession of small amounts of hard drugs in Oregon, is almost certainly at an end. Voters passed the measure by a wide margin in 2020, but later soured on it, and legislators, both Democrat and Republican, recently approved a bill to make minor drug possession a misdemeanor crime again.

The debate leading up to the bill’s passage was principally one about how severe the penalty should be for drug users who resist treatment—30 days of jail time (Democrats) or 180 days (Republicans)? (They settled on 180, but with multiple chances for people to get into treatment before going to jail.) It is not a terrible bill, but the squabbling over jail time for those who don’t want treatment belies a bigger issue: policymakers never really figured out how to get even the drug users who do want treatment into treatment. They make up only 20% of users outreach workers and police officers encounter, they say, but it still seems sensible, if not essential, to figure out how to get them into treatment before attempting to get the rest in as well, as any problem with the former is likely to be exacerbated with the latter. (I will devote the entire next piece to the question of what to do about the people who resist or refuse treatment, the other 80%.)

The good news is that even though policymakers couldn’t figure it out, regular people could: police officers, peer support specialists, and others who work in treatment and recovery services. They did not hire an expensive, out-of-town consultant to write a report and make a recommendation, and they did not wait for the Oregon Health Authority to come up with a new plan. Instead, they talked among themselves and piloted their own program to try and solve one of Measure 110’s biggest failures. May policymakers please learn from it.

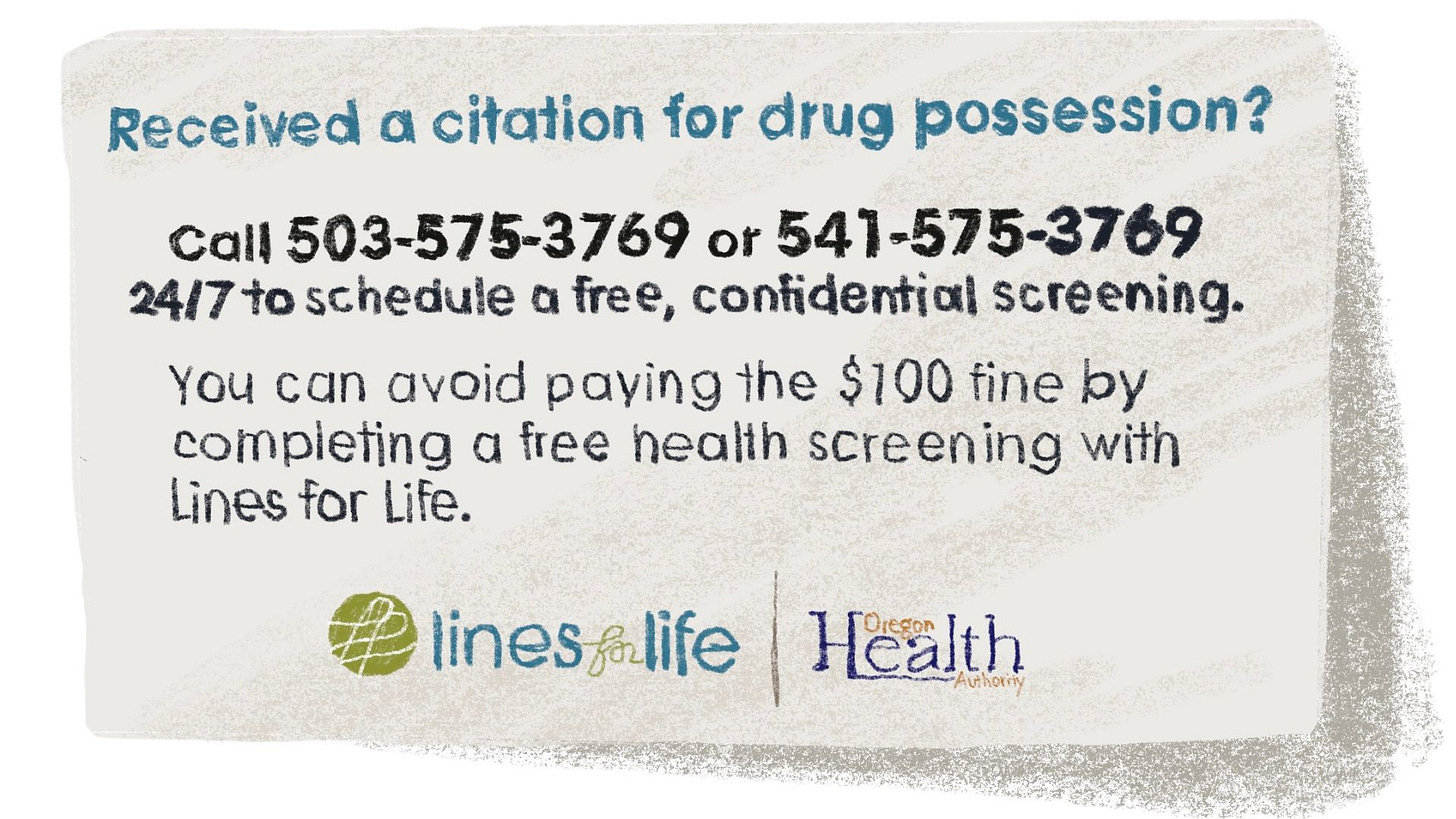

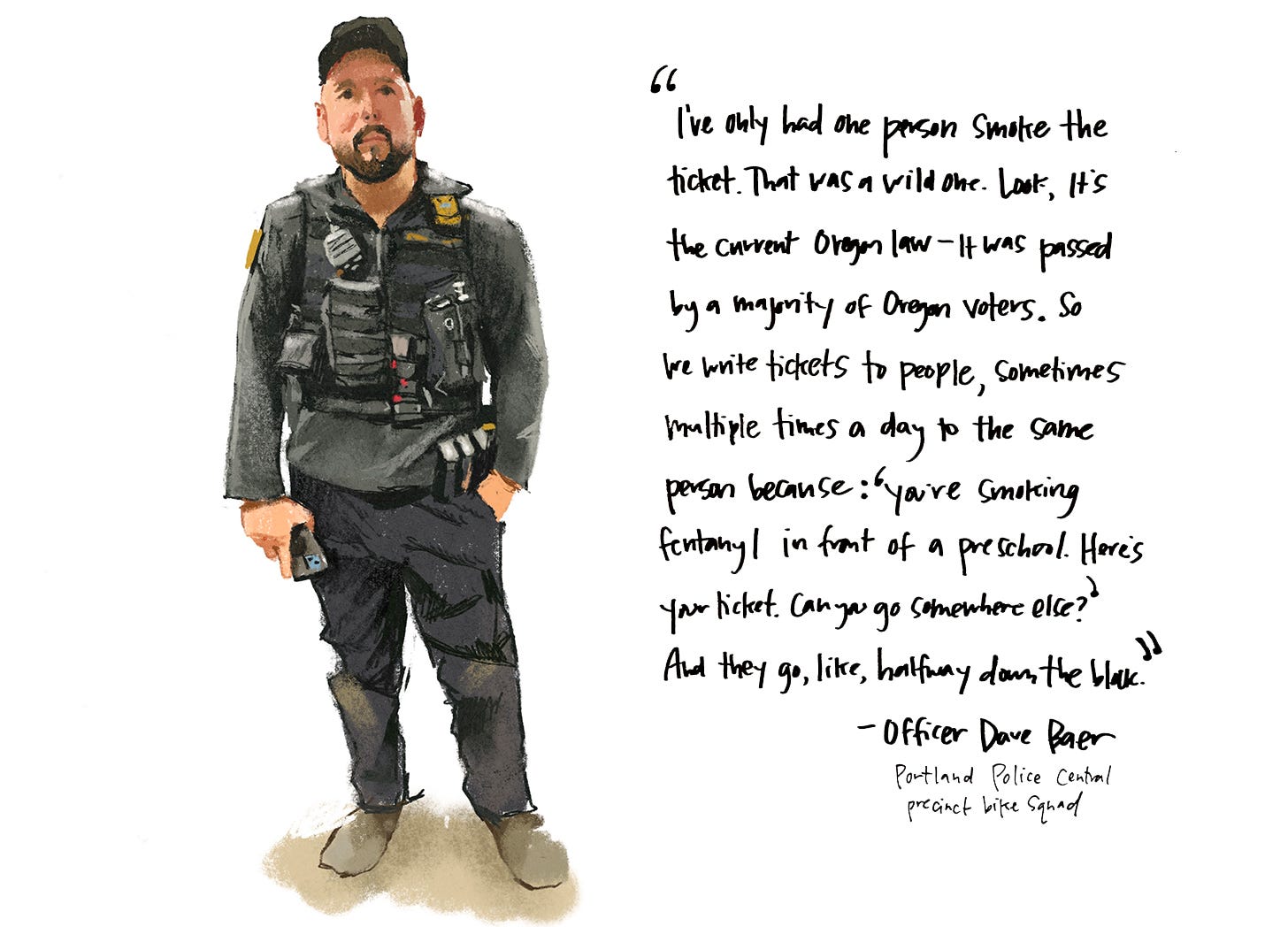

SINCE MEASURE 110 first went into effect, in February of 2021, this is mostly how it’s gone: A police officer, like Dave Baer, rides around downtown Portland on his mountain bike and sees a man smoking fentanyl or meth, which is not hard to do—people are doing drugs all the time, all over downtown—and approaches him and writes him a ticket for $100. Then he hands the man this card:

—and tells him he can call the number on the card if he wants to get into treatment, and even if he doesn’t want treatment, as long he calls the number and completes a health assessment, he can get the $100 fine waived. (Legislators later amended this, rendering the assessment not necessary to get the fine waived.) Most of the time, the drug user says thanks and returns to his drugs.

It’s almost impossible to overstate how ineffective, unsuccessful, and truly catastrophic this part of Measure 110 has been. Only 4% of people cited ever even called the number on the card, and no data was collected on whether those people ever made it into drug treatment after calling. As of June 2022, only 119 calls had been placed to the hotline. Every single one of those calls cost taxpayers $7,000.

Anyone who was paying attention could see the citation system wasn’t working, and for anyone who knew anything about addiction, it was not a mystery why.

But if that person has to call a hotline, listen to hold music, talk to the operator, then call the first number the operator gave him, answer questions about his insurance, put himself on a waitlist, call the second number, no one answers, then call the third number—the window closes. Overwhelm sets in. Withdrawal symptoms begin. This person feels hopeless. How to escape feeling hopeless? By doing drugs again.

Joe Bazeghi knew there needed to be a way in which anyone in those short, fleeting windows of willingness could easily and immediately begin treatment. He mentioned this to Sgt. Aaron Schmautz, president of the Portland Police Association, while they were in Portugal together last fall, along with other service providers, elected officials, and people in law enforcement, learning more about how drug decriminalization worked there, and Sgt. Schmautz agreed. They had observed several things in Portugal that explained its success—police there are not seen as an enemy, but as a resource; police officers have real-time access to data about what services are available; and behavioral and medical services are integrated because Portugal has public healthcare—and as they discussed these things over custard tarts one night in Lisbon, the idea for a pilot program in which service providers were partnered with police officers began to take shape. “Neither of us said anything novel,” said Sgt. Schmautz. “We didn’t need to do anything new to work together—we just needed to work together.”

Meanwhile, in Portland, Officer Baer gives a talk at the conference No Time to Spare: Confronting Oregon’s Fentanyl Crisis—“I show up with a powerpoint about the bike squad, and it’s a packed house; there are all these people there with the alphabet after their name and I'm like, “Oh hey, I'm Dave Baer, I ride a mountain bike…”—and just before he leaves, Tera Hurst with the Health Justice Recovery Alliance stops him and asks if he’ll meet her for coffee to talk about an idea she has. She also wants to pair cops with service providers. Officer Baer agrees to meet her and Janie Gullickson, of the Mental Health & Addiction Association of Oregon, and when he does, he agrees to try out their idea. Later, he panics—did he accidentally exceed his authority by authorizing participation of the bike squad in a new pilot program without talking to his superiors first? He calls Sgt. Schmautz who laughs and says he’s been trying to start the exact same thing…

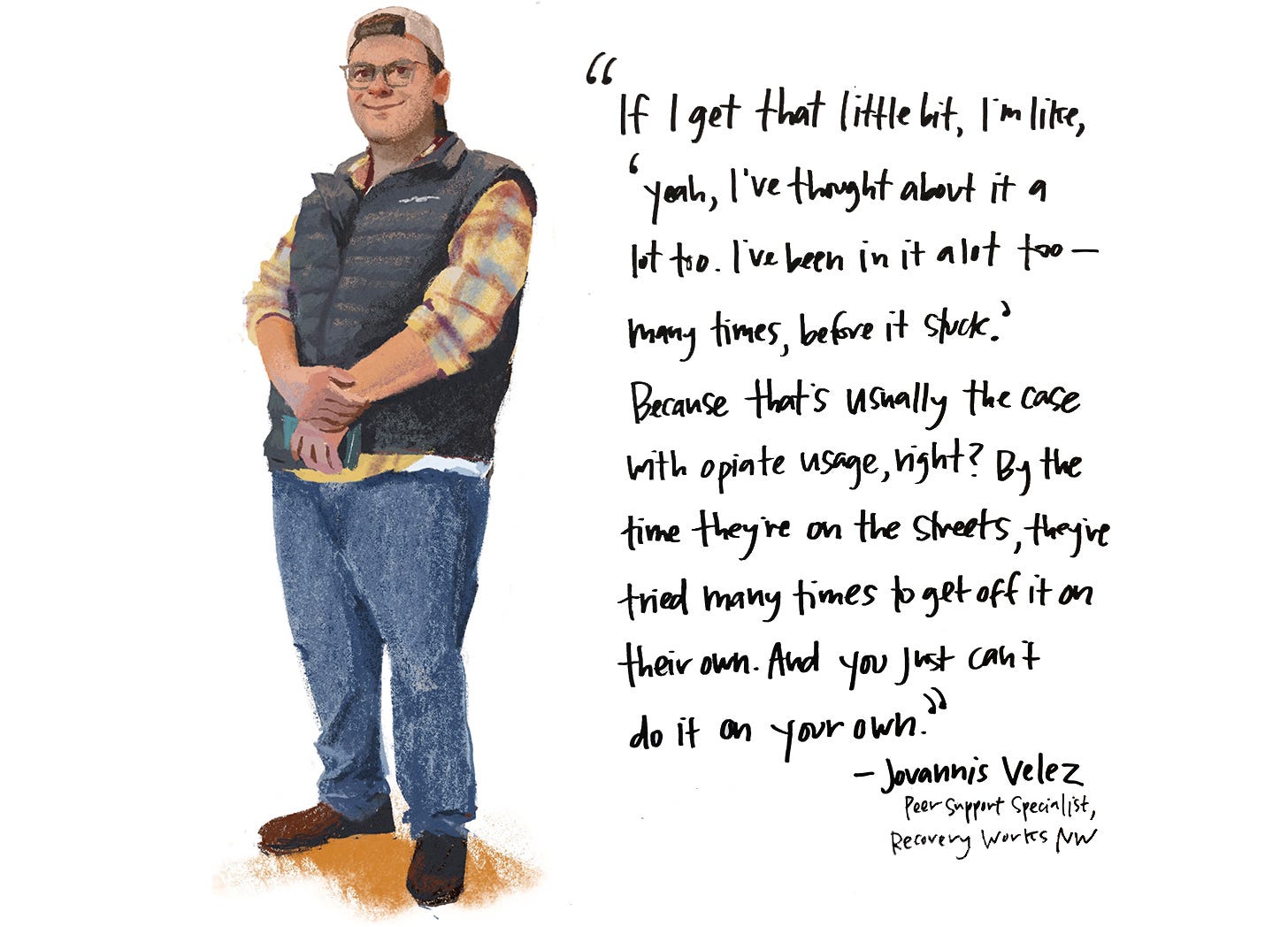

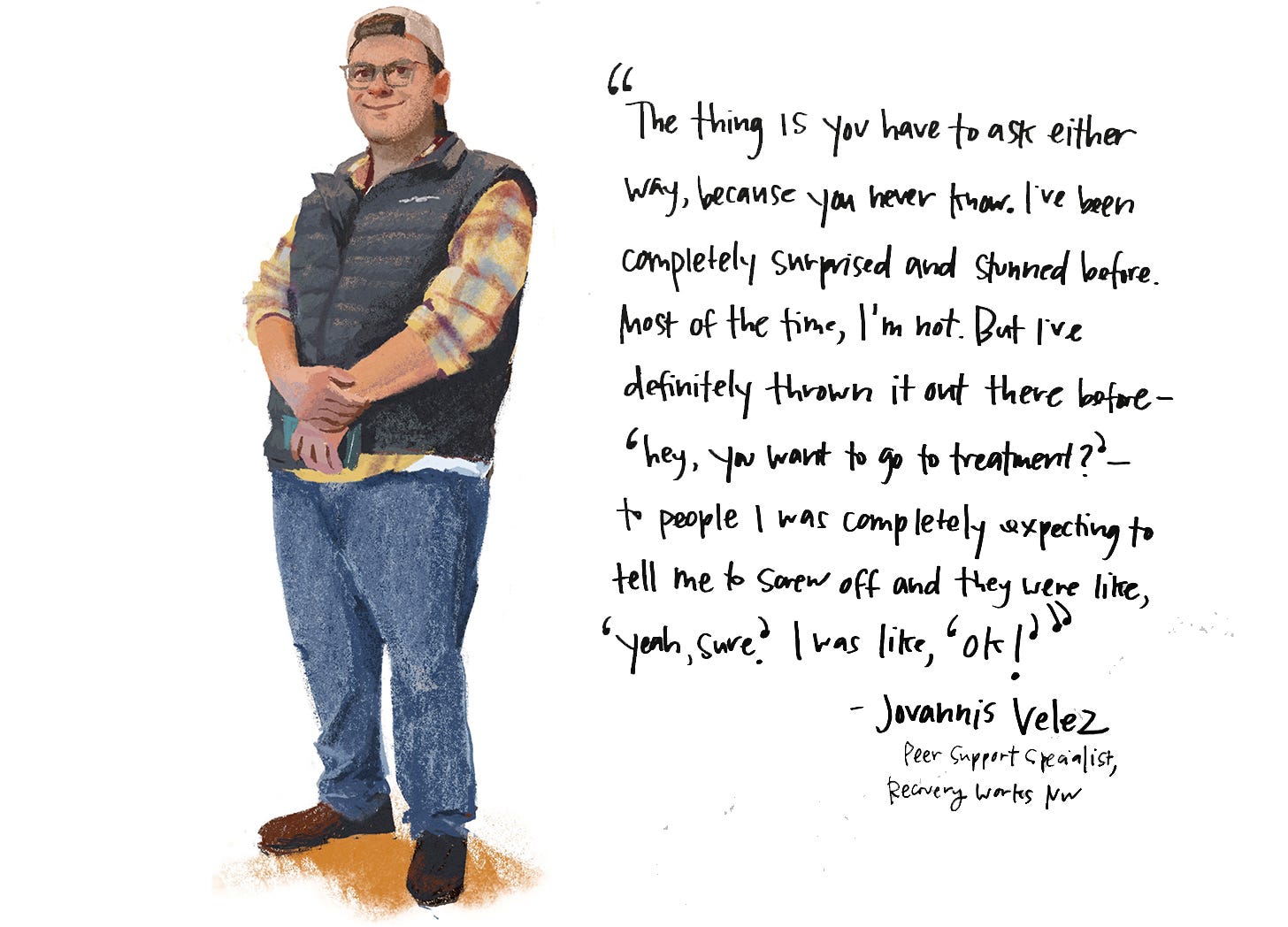

Here’s how the pilot program works: Officer Baer rides around downtown Portland on his mountain bike, sees a man smoking fentanyl, approaches him, tells him he’s getting a citation for drugs, and then asks if he wants to go to treatment or even talk to someone about going to treatment? If he says yes, Officer Baer calls the group of peer support specialists (people in recovery) who are standing by (sitting, actually, around a conference table at the Behavioral Health Resource Center), waiting for a call. At least two of these peer support specialists arrive within ten minutes, and if the man says he’s maybe thought about getting into treatment, maybe, they have enough to begin.

Most of the time, the person smoking fentanyl or meth is surrounded by other people, which is great from an outreach perspective. Jovannis talks to all of them.

If the man smoking fentanyl just wants to talk about treatment, fine—Jovannis doesn’t pressure him. The point is to establish contact and build a relationship so that in a future window of readiness, he’ll know help is available. (This man might be in the 80% of drug users who decline services today, but in the 20% who accept them tomorrow.) If he does want to go to treatment, the specialists know exactly how many beds are available and where those beds are and they can go pretty much right away.

On the first day of the pilot program, Officer Baer encountered 67 people who were smoking drugs in public. Of those 67, 17 were interested in talking to someone about treatment, and one person actually went to treatment. It’s so hard to get someone to do this, and it so rarely happens, that Officer Baer considers getting just one person into detox a success.

This person went to a new detox center that’s only been open since September—the state’s first that was made possible with money from Measure 110. (Measure 110 money cannot fund treatment that is reimbursable through Medicaid, but it can pay for more places for treatment to occur; Recovery Works NW used the funds to purchase and renovate buildings, and recruit and train staff.) He stayed only a few days, as most people going through detox do, then transitioned to an in-patient program, and is now in training to be a peer support specialist.

He is one of the lucky ones who happened to be in a window of readiness on a day in which the pilot program was running—only every other Thursday right now. If a cop comes across someone who wants to go to treatment on another day, that cop will often call Officer Baer and ask him to send the service providers, and Officer Baer has to tell the cop, sorry, the pilot program isn’t running right now. And all the cop can do is give him the card with the phone number to the hotline.

It’s not yet clear what will happen to the pilot program come September, should Governor Kotek sign HB 4002 into law, but to Joe, it does not look good. “If we move back to criminal sanctions,” he said, “we're not going to be able to participate with the police in the same way.”

So, what to do about the other 80%, the ones who resist or refuse services? Stay tuned—that’s what my next piece is about, coming the week of the 18th!

I got a root canal yesterday, and the dental assistant (and one of the Portland Stack’s newest subscribers!), Angie, had so many great questions for me: What’s the real reason Measure 110 failed? What do I think of the new bill, HB 4002? Should drugs be decriminalized or not? Do most people who are using drugs downtown want to get into treatment or do they just want to keep doing drugs? What should we do to get out of this terrible crisis?! Usually, I’m the one asking these questions, not answering them, so I’m always taken a little off guard when someone asks me what I think, but I do have thoughts! Objectivity in journalism is such a myth—of course we have opinions, assumptions, and individual experiences that shape our worldview and that we bring with us when we’re reporting. All we can do is be honest about them, and challenge them when they get in the way of the seeing the world as it actually is. (I had this line taped to my wall for years and it still applies: “You got to just keep breaking down who you are, so you can more and more appreciate the world that you’re looking at.”) So, here are my thoughts, for Angie, and for whoever else may be interested. First, for this new drug law to be successful, what matters more than anything is…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Portland Stack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.