The Herculean Effort It Takes to House One Person in Portland

Shortly after taking office in January, the new Chair of Multnomah County, Jessica Vega Pederson, announced her plan to house 300 people by the end of the year. It’s now October 6th, and they have housed only 18. Why is it going so poorly? It’s not because the county does not have enough money—in fact, the last two fiscal years, it’s had more money than commissioners have been able to spend, with $50 million left over in 2022 and $42 million in 2023. And it’s not because there isn’t the political will. Portland area voters overwhelmingly passed the Supportive Housing Services tax in 2020 and consistently report that homelessness is their number one concern.

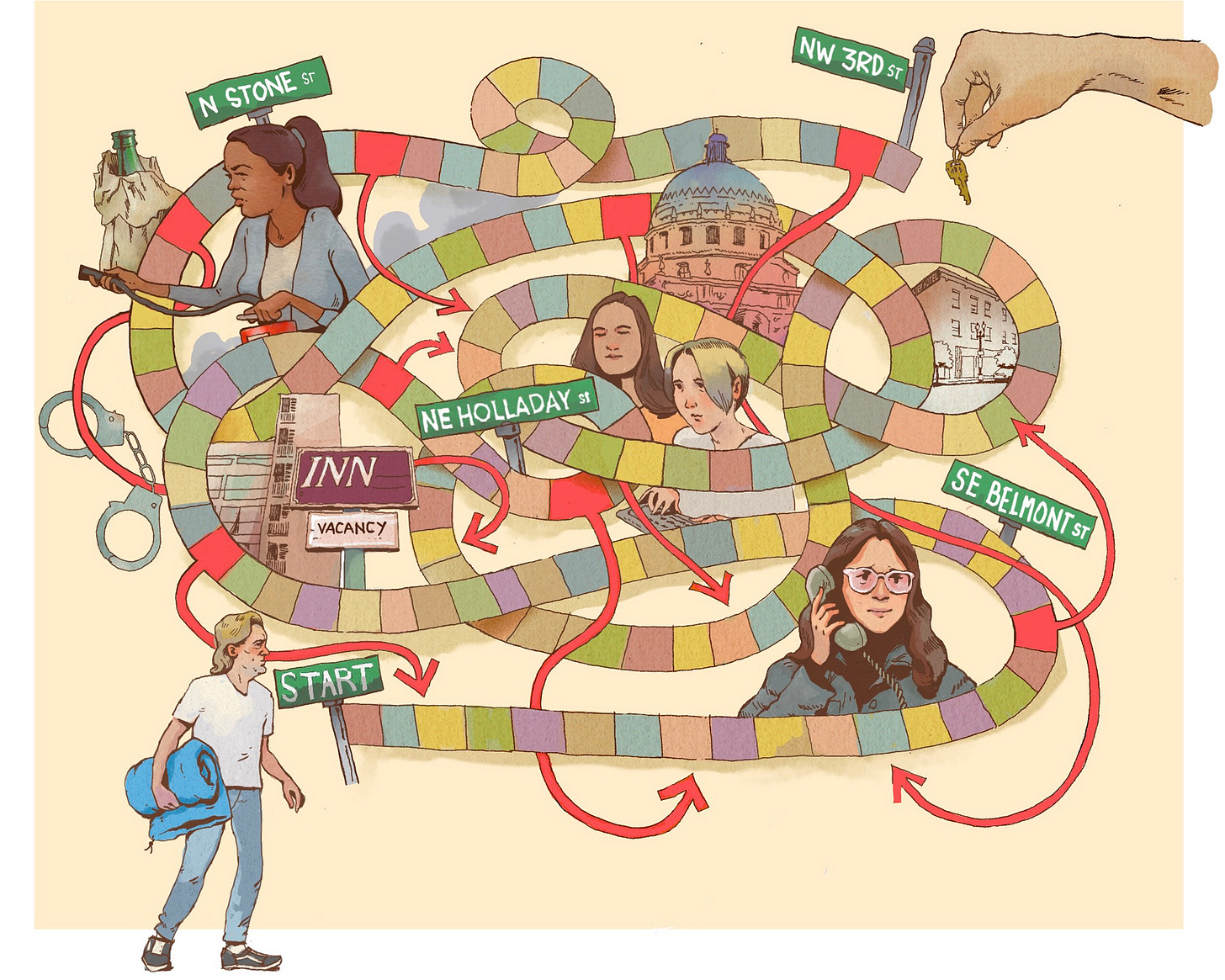

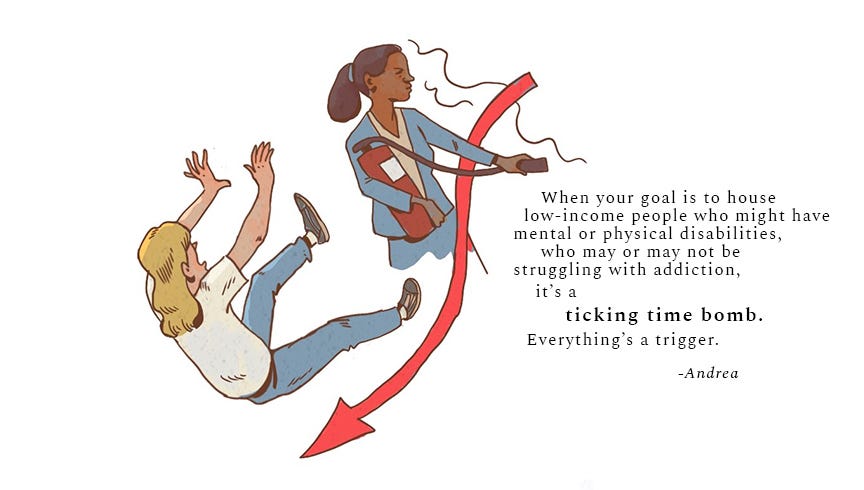

Those involved say the reason it takes so much time and effort to house people is because of barriers. This is mostly accurate, although vague, and there is an upside as well as a downside to using such a nebulous term. Certainly, it’s easier to convince voters to spend taxpayer money on housing someone with “barriers” as opposed to housing someone supporting his fentanyl habit by robbing Target, for instance, but it also breeds a kind of bewildered impatience, if not fury, in voters who are right to wonder what is taking so long?! as they’ve been told that all that’s between most houseless people and housing are small, external obstacles like a credit reporting error or a lack of furniture. Rarely is that the case. The things that often make it easier to survive outside are the same things that make it harder to get back inside, and the more of these things a person picks up while houseless—criminal convictions, drug addictions, behaviors that make sense on the street but nowhere else—the more likely it is that the process to get them housed will be long and complicated and look like this:

Mark McCarthy is 61 years old, and has been houseless for either 17 or 20 years—it’s been so long, he honestly can’t remember.1 He did get housing once during this time with the help of JOIN, but his neighbors downstairs threatened to burn him out and kill his cat, so it didn’t last very long. Then he went back to living outside, most recently in the alcove across the street from the Suzette Creperie on Belmont, but he’s had problems with neighbors here too.

This was true—he has ADHD, bipolar disorder, and no teeth—but he was also about to come into a bit of luck, and get back on track to get housing again. It happened one day in the late summer of 2021, when he was going to take a shower at Groves Church, which opens up its facilities three days per week to people who need them.2 An exceptionally dedicated person named Marisa was volunteering that afternoon, checking people in and cleaning the showers, but she also worked full time at Northwest Pilot Project, and she told Mark she could get him a phone interview with a case manager there.

Northwest Pilot Project helps people find housing, but only people who are over 55 and low-income. Mark is both, but, Marisa explained, he’d still need to get through a phone interview (and for this, he’d need a phone—fortunately, his friend Sandy, who volunteers with Beacon PDX, agreed to let him use hers), because the case managers are swamped and thus, being extra selective, only taking new clients they think are truly the most vulnerable. Luckily, Mark has had two heart attacks and been living outside for a length of time even NWPP considers long, so he makes it through the interview and gets a case manager!

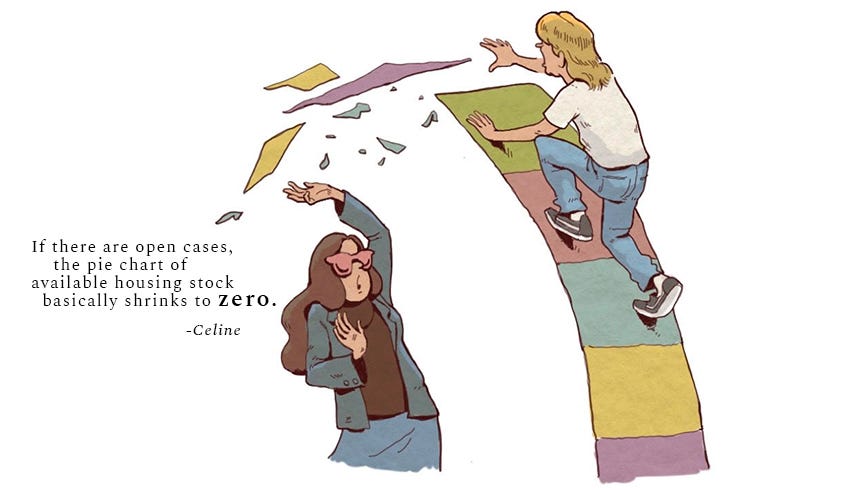

The first thing Mark’s new case manager, Celine, does is a background check so she’ll know to which buildings Mark should apply: the more extensive his record, the less housing that will be available to him.3 It comes back quickly, and it is not good. Mark has several convictions in Oregon and, worse, an open case in Arizona.

It’s now October, and it’s starting to get cold. Mark doesn’t think he can make it another winter outside, and Celine doesn’t think she’ll be able to resolve the open case anytime soon, so she motels him. (Motel is a verb in this world.) He gets into his room and sleeps for three days straight. When he wakes up, there is color in his face for the first time in years.

Meanwhile, Celine tries to contact the Pima County Attorney’s Office in every way she knows how: she emails, she calls one number on the website, then another. No one responds. She tries again, and still, no one responds. So much time passes, she starts wondering: “Who do I know in Tucson who can go knock on the County Attorney’s [door] and be like, can you just tell us what is going on with these charges?!”

Since it seems no resolution is in sight, Celine tells Mark he may as well apply for an apartment at the one building she thinks he might have a chance at getting into, even with an open case on his record. (He could also get into transitional housing at this point, but Mark doesn’t want to because 1. he’d need to be sober, or at least be willing to try and be sober4 and 2. he wants his own, private space, not a shared room.) He applies at the building Celine suggested, but it’s in the process of switching management companies, so it will be several weeks before the new property manager runs his application. When she finally does, the open case somehow does not come up. (Or it does but the screening company doesn’t report it to the property manager? Celine’s not about to ask questions: “I'm a little bit thinking it was kind of a miracle.”) But a criminal conviction for disorderly conduct does come up, and it’s on this basis that Mark is denied.

Like all low-income buildings in Portland, the Musolf Manor uses rental criteria at least partially set by the city. But this, in some ways, is a formality. The requirements—no evictions or drug-related misdemeanors in the last five years, no charges for theft or criminal trespass in the last three—are too stringent for most of the Musolf Manor’s applicants, so they are encouraged to submit documentation asking management to make an accommodation and overturn their denial, and this is exactly what Celine and Mark do.

Celine’s strategy in writing letters like this is to connect a client’s disability to the specific charge, because fair housing laws make it illegal for housing providers to reject someone because of a disability. She also asks two of Mark’s friends, Hannah and Lydia, to write letters on his behalf. Sadly, this is not something Celine’s always able to do: some of her houseless clients are no longer in contact with their families, and they do not have any friends. Mark has many friends. They are mostly smart, strong, exceedingly capable women—graduates of Mount Holyoke and Ringling, the founder of the shower project (Hannah) and the writer of two critically acclaimed novels (Lydia)—who might not initially seem like the most ideal audience for some of his more brazen observations (“her mom was a math teacher—a woman math teacher!!!”) or lewd interior design choices (his walls at the motel are plastered with centerfolds), but Mark is so genuine and open and utterly captivating, he makes friends wherever he goes. And when he does, he starts scouring the free piles for them. Also, the street. He is an extremely generous person and he loves to give gifts: muffin pans for Hannah, who likes to bake, and children’s books for Lydia, who has two little girls. They mention this in their letters about him, among other things—his resilience, his resourcefulness, his empathy—and then send the letters off to the Musolf Manor, hoping it’ll be enough to get Mark in the building.

Before Andrea5 started managing low-income buildings like the Musolf Manor, she worked in resident services, also in low-income buildings, and her management style very much reflects this. She is kind, but firm. She knows a man upstairs saw his friend die suddenly two weeks ago, and even though he’s been clean 16 years, this is the kind of thing he could lose it over. She plans to check on him later. She also knows that another man, who sneaks in the building one morning behind a resident with a door tag, does not have an apartment here, and she has to bolt from behind the front desk to stop him before he gets to the stairs and cut him off a minute into his stammering that, uh, his mom lives in the building and he should be on the lea—he is not, and Andrea knows he is not. She ushers him back outside.

Her first goal, as the property manager of a low-barrier building, is to make it as easy as possible to get people who would otherwise be denied housing housing. Her second goal, once they’re housed, is to make sure the building is a safe place for them to live. This is not as simple as it seems, as it’s not uncommon for the second goal to be in direct conflict with the first: Some people who need housing are not considered safe to house with other people who also need housing, and this is one reason the Musolf Manor has low barriers and not no barriers.

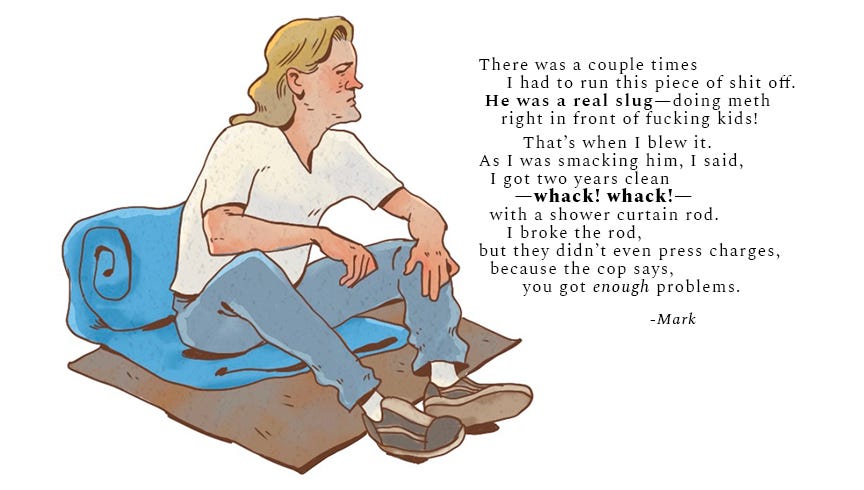

Given this, it’s easy to see why Andrea might pause before bringing someone into the building who has a history of being disorderly. There is enough disorder in the building as it is. Some of the formerly houseless residents let their currently houseless friends move in with them and some of these friends do fentanyl and then run down the hallway, high and naked, and Andrea has to chase them until she gets ahold of someone on the Behavioral Crisis Hotline. One resident, diagnosis unknown, recently banged his head against the walls so many times, he took his apartment down to the studs. A number of residents have started fires in their units. There was also the time Andrea tried to protect one resident’s laundry from getting stolen and then got slapped in the face while wrestling it away from the thief who’d crept in the front door.

According to the rental agreement, much of this is technically grounds for eviction, but in Andrea’s experience, evicting a tenant in Multnomah County is very difficult. (She feels the last thing a judge wants is to make someone else homeless.) She remembers one former tenant the other residents called the Building Terror who dealt drugs in front of the front door and thus, created a kind of constant traffic jam of addicts there that made other tenants feel uncomfortable, even afraid, to enter and exit the building. When the tenants mentioned this to her, she threatened to sic one of her customers on them; when Andrea tried to talk to her about it, she called her the N-word. Somehow this didn’t seem like it would be enough to evict her, but luckily for Andrea, the Building Terror also didn’t pay rent for a year. This still didn’t seem like it would be enough to evict her, but it did at least seem like enough to proffer a deal—Andrea would forgive all unpaid rent, and the woman would leave. Also, Andrea would omit the “eviction” from the Building Terror’s record, which she admits is not great for the next property manager, but what else is she supposed to do?

She could become skeptical, even suspicious, in reviewing requests for accommodations like Mark’s (and to be fair, it wouldn’t be totally unreasonable if she did—Mark was drunk at the time of the disorderly conduct charge and still drinks and was recently briefly banned from the Shower Project for showing up there drunk and getting into it with a volunteer), but remarkably, she isn’t. She remains totally committed to giving people a chance—maybe they completed a tenant’s education course with Rent Well or have 90 days clean in Narcotics Anonymous or recently signed up for a class at a community college? She accepts pretty much anything that shows applicants are trying to improve themselves. As this is exactly what Hannah, Lydia, and Celine’s letters say about Mark, they work. The denial is overturned and the Musolf Manor offers Mark housing! His rent will be 30% of his income or approximately $200 per month.

Celine, Hannah, and Lydia are thrilled. Mark is a little nervous. He has now been in a motel for more than four months and has gotten accustomed to his big room with two queen size beds. The studio apartment at the Musolf Manor only has room for one twin size bed, and is so tight on storage, the former tenant hung a rod above the toilet for clothes in lieu of an actual closet. (Otherwise, the building is a rather charming, recently-ish renovated hotel, built in 1910, with many historic elements preserved including the handrails, windows, and original hotel sign.) But the bigger problem, again, for Mark, is the neighbors: “People are getting high down there!” It’s not clear if this panic stems from fear he might be tempted to use again or if it’s fear for his own personal safety and security (recall the neighbors who threatened to burn him out and the slug who did meth in front of kids and enraged Mark to the point of a fight), but regardless, it’s very real, and Mark says he’s not moving.

Celine reminds Mark this is a good opportunity to build rental history that could help him eventually get into another building in a less chaotic neighborhood. Hannah and Lydia tell him the same. Eventually, the fear subsides. He agrees to go. Northwest Pilot Project hires movers, his friend Sydney brings him a dresser, and she and Hannah help him unpack at his new place.

On April 1, 2022, approximately seven and a half months after he first started the process to get housed, Mark moves into his own apartment!

EPILOGUE

Just a few months after Mark moved into the Musolf Manor, Celine finally managed to get Mark’s open case in Tucson dismissed through tremendous effort, tenacity, and a series of serendipitous events.

These events also begin at the Shower Project, when it was featured, in the spring of 2021, in this article which District Attorney Mike Schmidt read and liked. A few months later, he met with Hannah and told her if there was anything he could to help, to let him know. And she did—she and Celine needed help getting in touch with the County Attorney’s office in Tucson. Would his office help with that? They said they would.

First, the District Attorney’s executive assistant, Jillian Detweiler, tried to contact the Pima County Attorney’s Office, and like Celine, got no response. So Mike Schmidt somehow managed to track down a cell phone number for the County Attorney in Tucson, Laura Conover, who connected Celine with a detective, Fabian Pacheco, who then put Celine in touch with a prosecutor who submitted a request for dismissal of Mark’s case and, then with a quickness unprecedented in the entire process, a judge signed off on it the very same day.

Once the open case was resolved, Mark’s options for housing increased. He also now had six months of rental history, and, most importantly, he had, as the manager of his new building said “great supporters” in Hannah, Lydia, and Celine. When Mark was initially denied at this new building, their letters helped to reverse the denial again, and in November of last year, he moved into this new building which he likes much better: it has a computer room, library, rooftop deck, smoking patio, and neighbors with whom he only has mild conflicts. He’s now been housed a total of 18 months, and is currently trying to adopt kittens.

REPORTER’S NOTEBOOK

I met Mark in the spring of 2021 while I was volunteering at the Shower Project, and was instantly transfixed by the way he talked about things both hilarious and heartbreaking; here he is on his look: “I used to have big arms and long hair—Billy Ray didn’t have shit on me” and then again, on losing his great love, Terry, to a morphine overdose: “I knew when I heard the news, I would never love a woman in my life again, and to me that was like cutting off my legs in a fucking marathon.” Mark is truly a tender, complicated person: kind, empathetic, and wildly generous, forever finding things on the street or in the free piles for the people he cares about (including my baby, to whom he once gifted a stuffed sloth); also, stubbornly alcoholic and erratic, occasionally threatening to fire Celine or telling the women in his life “we’re history, and I mean history” when they won’t drop everything to drive across town and buy him cigarettes. He’s my favorite kind of person to write about, and I’m very grateful he let me.

When I heard he was going to get a case manager to get housing (not everyone who came to take showers was as motivated), I was thrilled for him and I followed along with great interest. But I was alarmed and very concerned to see that the process to get him housed took so much luck and serendipity and what seemed like a series of small miracles. We are truly in trouble if we’re to rely on the unlikely events that district attorneys will have each other’s cellphone numbers or screening companies will always make mistakes to house every one of the thousands of people in Portland who need housing.

But as long as the plan is to move people from the street directly into permanent housing, without any transitional housing or treatment in between, this predicament will likely persist. (Transitional housing is not as concerned with criminal convictions, because it requires treatment that would, in theory, address the behavior that led to the charges.6) If we can infer anything from Mark’s story, it’s that the barriers many houseless people face—complex criminal records, addictions, unstable ways of dealing with people, like whacking them with a shower curtain rod etc.—are often bigger and more intractable than the buildings they’re meant to move into can handle. This is true even when there are services available, as the services are for whoever wants to access them and not everyone does. These buildings are not likely to do away with background checks and the lengthy appeals process they trigger anytime soon, because, as Andrea said, they’re ticking time bombs, and the last thing they want to do is let someone in who might set the whole thing off. Even Mark wants to keep some of the barriers in place, because he doesn’t want the slug who does meth in front of kids or the people getting high to be his neighbors anymore than anyone else does—probably more so because he’s likely to be impacted more by their behavior than a person who can install security systems or build gates or simply move to another building or house.

Housing First, the model that Portland and pretty much every other city on the West Coast has adopted to try and solve homelessness, is based on the idea that people need the stability and safety of housing before they can confront and recover from substance abuse, mental health disorders, trauma etc. Also, that people will confront their addiction and mental health once housed and accept services that are offered to them. It’s the second part that’s tricky. Mark is certainly safer and more stable indoors than he was outside (and he has teeth now!), but he is not sober, and when Celine arranged for him to go to detox, he showed up drunk, refused protocol, and left.7 His former neighbors whose guests run through the halls on fentanyl are apparently not interested in treatment at this time either. I imagine the same is true for the Building Terror, although I didn’t speak with her, I’m only inferring from accounts of her behavior that she needs some kind of intervention, if not for her own sake, then that of her neighbors.

As the crisis continues, this part of the model—that services are voluntary, not compulsory—is increasingly at the center of contentious debate in Portland, Seattle, Los Angeles, and especially San Francisco, which is currently fighting an injunction that prohibits moving people off the street, even when they decline shelter. All of this raises really interesting, important questions about autonomy, addiction, compassion, choice, public safety etc. that I am intensely curious about and will be exploring and reporting on here on Substack. If you learned anything new by reading this piece, and feel that you understand what’s going on in the world even a smidgeon better than you did before, please consider becoming a paid subscriber by clicking this red button ↓

Thank you!

Mark was not housed through Housing Multnomah Now. I wanted to write about someone who got housing through the program, but Transition Projects, the sole provider, wrote me via email they were “currently unable to make [my] request to speak with a Case Manager happen.”

The name of the church is technically Sunnyside Methodist Church, but the Groves congregation runs it and allows the Shower Project to use the facilities.

Mark’s first case manager, Yvonne, left the Northwest Pilot Project not long after Mark began working with her. Her supervisor, Celine, then took over. To avoid confusion as there are a lot of characters in the story, I only use Celine’s name.

Mark had recently tried to go to detox, but refused anti-seizure medication (he was worried it would complicate the issues he has with his heart) and left after two days.

Andrea is a pseudonym for a composite character based on three property managers I spoke with for the piece, as Pinehurst Management, the company that manages the Musolf Manor, “does not permit interviews with the media.” Innovative Housing, the non-profit housing corporation that owns the building, also turned down several requests for even the most basic information about how the application process works, what the rental criteria is, and if there are alternative terms for tax credit buildings.

The exception, for some places, is for sex offenders which they do not accept, because they serve children.

Unfortunately, the day Mark was ready and scheduled to go to detox, the Center suddenly didn’t have enough beds available, and the window of willingness seemed to close. He also went to detox twice in January of 2023, but at least one of those times, left before discharge. He currently has a little over 100 days off whiskey, but not beer.

Devin, I really loved this-- I historically lean away from reading long-ish pieces about civic issues, but you kept it compelling and informative through and through.

Informative and thorough piece. Glad you're out there painting the whole picture!