What really happened in this election

Low voter engagement wasn't about ranked choice voting—it was about the 400% increase in the number of candidates who ran.

The results of the first election under the new reforms were certified yesterday! A quick reminder of these that relate to the way we vote:

Voters previously elected city councilors citywide by voting for one person. Now voters elect three city councilors in the geographic district in which they live using a form of ranked choice voting called single transferable vote.

There used to be four city council seats—now there are 12. (The Mayor previously served as the fifth member of city council. Now he will only cast a vote to break a tie.)

There used to be primaries. Now there aren’t.

All of these reforms were supposed to increase participation among voters and candidates who have historically faced barriers either to voting or running for office. A bigger city council meant more people would run in general and a lower threshold to win a seat (25%+1 of votes) specifically meant more people who historically might not have run because they didn’t have the money or political clout to do so, would. This bigger, more diverse pool of candidates was supposed to excite voters who are generally not involved in local politics. To ensure these less-involved voters’ voices were heard, primaries were eliminated, because these voters, like all voters, are much more likely to vote in a general election in November than a primary in May. All voters were going to have more choices, and more choices are what voters want. In the end, city council would be more representative of the city it serves.

It’s true, we are only one election in, and thus, the sample size for analysis is small. But let us look at the results we have, and contrast it with the results the reforms were meant to produce. Across the city, approximately one in five voters left the city council section on their ballots blank. In District 1, which has the most low-income voters the reforms were specifically meant to serve, nearly one in three voters left the city council section of their ballots blank. Only 56% of registered voters in District 1 voted at all, which means that just 39% of eligible voters there were involved in electing their representatives to city council.

Clearly something went awry in voter engagement, and to find out what this was, I went to the parking lots of the Dollar Tree, Rite Aid, Safeway, Plaid Pantry, the post office etc. in District 1 and talked to nearly 50 eligible voters about why they voted or didn’t, and what they thought of ranked choice voting, their ballots, and the many choices they had for city councilors.

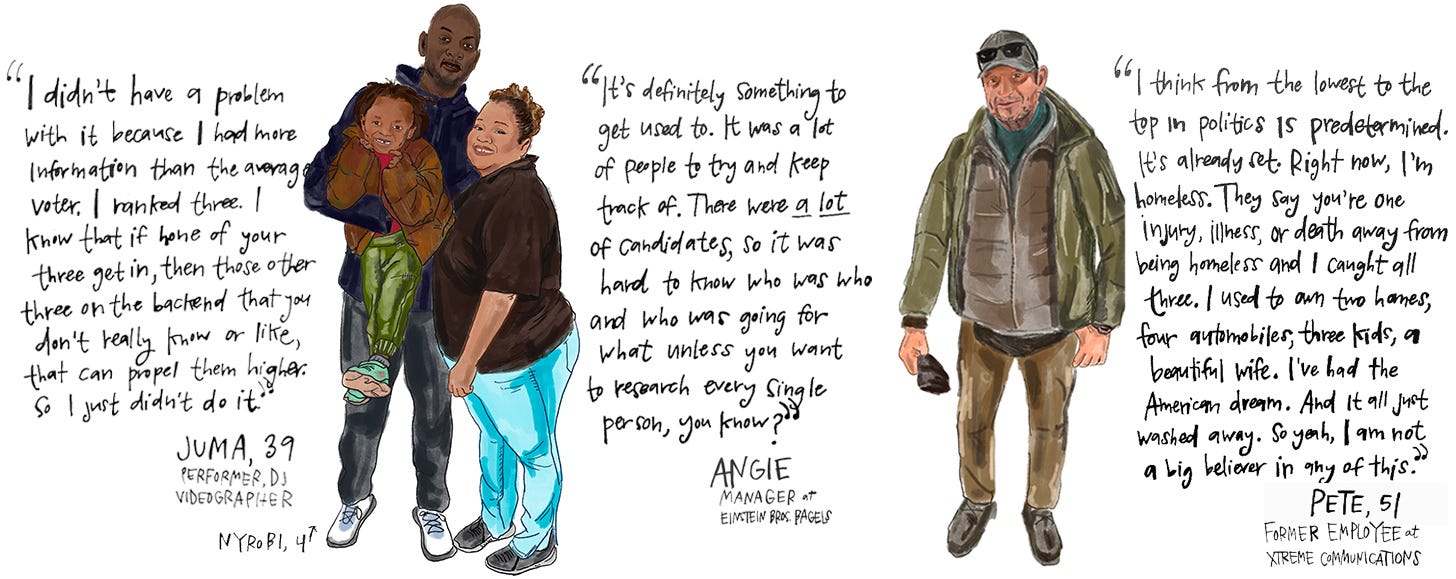

This is but a small sample of the voters and non-voters with whom I spoke. Here’s a summary of my findings from talking to almost 50 of them:

Pretty much every voter I spoke with said they felt overwhelmed when they looked at their ballot this year. (“I lost my mind!” an 18-year-old barista told me.) But when I asked them what specifically felt overwhelming—was it ranked choice voting or the number of candidates running?—almost all of them said the latter. The number of candidates who ran—16 in District 1, 22 in District 2 and 30 (!) in Districts 3 and 4—was so absolutely enormous it stressed voters out. (“I can’t deal with this!” one 26-year-old told her mother before giving up and deciding not to vote.) Even high-information voters, like Juma and Angie, who had a family member in the race, and thus went to multiple panels, forums, and events, saw candidates on their ballot they’d never heard of or seen before. The reaction to ranked choice voting was mixed—some found it “weird” or “confusing” or “not helpful” as Jason said, but more than half the voters I spoke with said the process of ranking candidates was “pretty straightforward” or “easy.” Note: Almost none of these voters knew about the specific form of ranked choice voting Portland now uses, single transferable vote (I directed this video and my husband animated it for a local nonprofit, explaining how this voting method works), but most of them said they didn’t feel the need to know more and it wouldn’t have changed how they ranked candidates.

The city awarded $675,000 to United Way of the Columbia-Willamette, of which $210,000 was given to community organizations like APANO, Latino Network, and the Pacific Northwest Museum of Queer Art to educate hard-to-reach voters on ranked choice voting. But the non-voters that I spoke with largely do not belong to community organizations. The correlation between non-engaged voter and non-engaged in general was very high. A few of the organizations who were tasked with reaching voters listed door-to-door outreach as part of their efforts, but mostly they hosted events (mock elections, town halls) and tabled at other community events that non-voters were unlikely to be at. A big difference between voters and non-voters/under-voters is that the former had at least one source of information they considered reliable (Ballotpedia, the Bike Portland podcast, Willamette Week etc.) whereas the latter largely told me they do not follow news and don’t know where to find news or information even if they were interested in doing so. “I watch T.V.—regular T.V.,” a cashier at the Dollar Tree told me. “And I didn’t see a single ad for anybody.” I asked him if he’d considered googling the city council race, and he said no.

A lot of media outlets and campaign staffers had a similar narrative to explain the low voter turnout among eligible voters in East Portland: they’d been neglected by City Council for years and were angry about it. “If you tell people you’re going to put in sidewalks for 30 years and you still don’t, people get mad,” a campaign manager told me. Certainly, some non-voters were bitter (see Pete, above), but to be angry at broken promises from local politicians, you first have to be paying attention to what the politicians are promising, and the vast majority of non-voters I spoke with were not. When I asked them why they didn’t vote, almost all of them answered as if the presidential election was the only one taking place. “I think first and foremost our state isn’t considered in the election,” a 28-year-old told me. “It feels like a moot point.” On the whole, the non-voters had not even considered that local elections were also taking place. They seemed unclear on what city council is in charge of and how it impacts their lives, and thus aren’t sure how they’d even decide which candidates to support. I asked Kelli if she just didn’t have time to look everyone up, and she said: “It’s not even time. I just don’t know.”

The lack of civic literacy in this city (and country) is so dire and so severe that if left unaddressed really could be the end of democracy. I’m always on a mission to help people understand the world we live in, and I consider this Substack to be a small contribution towards this goal, but after some of these truly troubling conversations, I’m also determined to get back into classrooms (high school, college, wherever) and teach students the basics of how their city, county, and state work. They don’t know—and how would they? Students need to take one semester of government to graduate from high school in Oregon, but the curriculum is almost totally focused on the federal government. They learn very little of how local government works, and what it has to do with their lives. I want to change this! If you want to hire or contract me to teach civic and/or media literacy, please send me an email (reply to this newsletter) or leave a comment below.

Meanwhile, this was one of the best and most interesting and meaningful stories I’ve reported in a long while. I met Bridget at Mail Room+ and burst out laughing at her response, but then noticed there was a long line behind me and ran off without even telling her the name of this Substack. To my delight and surprise, she found it the next day and subscribed! (Thank you, Bridget!) It’s such an honor to have her as a reader, I'm still glowing about it. When I met Jason, I asked him why he thought voter turnout in his district was so low. Before he could answer, another guy—young, blonde, on his way to buy a cigarette—stopped to offer his best guess. “It’s because we have so many homeless people here,” he said, “and they don’t vote.” And Jason got to tell him, “I’m homeless and I voted.” The young guy seemed startled by this and we all stood there for a minute, quietly watching his assumption dissipate right there in the Dollar Tree parking lot. I live for moments like this, and there were so many of them in reporting this story.

These are my thoughts on the election results as a whole:

One of the goals of the reforms was to encourage a more diverse group of candidates to run, specifically candidates who had never run before and were not members of Portland’s political class—and they did. Candidates ranged in age from 22 to 87, were both renters and homeowners, and had a wide array of professional experiences—one was a bus driver, another was a Portland bike cop, a few were climate activists, and several were small business owners. (A third identified as Black, Latino/a, Indigenous, or Asian, but note that city council was already racially and ethnically diverse—disproportionately so (of the four current councilors, two are Latino/a and one is Black; in the last council, two were Black and one was Latina) and somewhat socio-economically diverse, mostly because Portland offers public financing, which needs its own reforms, but has been successful in its original mission of diversifying city council.) But at the same time the reforms also made it much harder for these candidates to win, because with 98 (!) people running for city council, name recognition and political backing ended up mattering even more than they typically do. Of the 12 candidates who won seats, one is a current city commissioner, one is a former city commissioner, and another is a former county commissioner. Six others are/were staffers for former or current local elected officials.

The goal in eliminating primaries was to ensure that low-information voters’ voices and preferences were included in the electoral process. Like I mentioned, with so many choices, many voters froze and opted out of ranking a single candidate for city council.

*signatures to qualify to run.

The new council leans very left, if not far left. No one on the right was ever going to win in Portland (did any registered Republicans even run?), but many moderates did and they mostly lost. Here’s a diagram, made by Portland State Professor Eric Fruits, to help visualize where all the newly elected commissioners fall along the political spectrum. (This is highly subjective, and I’m sure someone else would make a very different chart—I’d love to see yours! Let me know how you’d line everyone up in the comments.)

The point of the reforms was to make Portland City Council more representative of Portlanders—and in many ways, I think they have. In a winner-takes-all election, only the majority ends up with representation, but proportional voting means that significant minority voting blocs will, in theory, also have at least some representation. When I say “significant minority voting blocs” I’m talking about political preferences. So, in each of the four districts, if at least one of the three councilors is moderate, the other two are far left or vice versa, i.e. the newly elected councilors in District 3 are: Tiffany Koyama Lane (far left), Angelita Morillo (far left), and Steve Novick (moderate); meanwhile in District 4, the newly elected councilors are Olivia Clark (moderate), Eric Zimmerman (moderate), and Mitch Green (far left). Thus, both moderate and far left voters in each district have representation on city council. Is it perfect? No. But neither was the previous voting method.

Finally, this is only the first election! So much more will be revealed as the newly elected councilors take office and govern in this new way. And there’s really only so much we can read into the results of one election—especially when we know that at least one voter was merely making a design.

I've covered the new charter for three years--so allow me to say that parroting the eyewash in the "Progress Reports," which you quote (without attribution) doesn't cut it. This came from a charter commission that was loaded with progressives, union shills, nonprofiteers...the usual reliable types. It had nothing to do with being representative.

The real purpose of the 3/4/25-percent idea was to get more minorities--specifically BPOCs--on the council...ignoring the ethnic makeup of the council they wanted to replace. If some sort of diversity was a goal, how come we wound up with three (count 'em) outright socialists? Woulda been nice if you dealt with the 12-member problem, which presented at the presidential election in which the mayor (and council) refused to obey the clear charter directive to resolve a tie.

As for your reportorial method--standing in parking lots isn't much of a survey. Also, at least you mentioned that your husband got a piece of the "inform the voters" pie, which was a standard, low-level machine giveaway. Which, typically, didn't work--but that was never the point.

It was just more money from me to thee.

And--golly!--I've just scratched the surface.