There’s a real dearth of civic literacy these days, so most people blame the Mayor, Ted Wheeler, for homelessness crisis we’re in, when in fact homelessness, mental health and addiction services are under the purview of the county, in particular the County Chair, Jessica Vega Pederson. But the Mayor does have some power, and as anyone who’s been paying attention knows, he’s been trying to exercise it as much as he’s legally allowed to, and here is the point—he’s not legally allowed to do much. Try as he might to enact and enforce a camping ban in Portland on sidewalks, parks, and public right-of-ways etc., he cannot. Here’s what stops him:

Q: Sorry, I’m confused. What happened exactly?

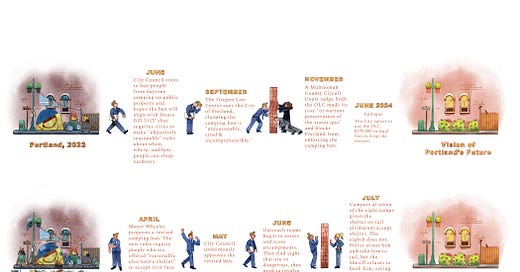

A: Mayor Wheeler has been trying to prohibit camping on public property and public right-of-ways in Portland for years now, but he keeps getting blocked. First, the Oregon Law Center sued him. Then a Multnomah County judge ruled in OLC’s favor, and prohibited the City from enforcing the camping ban, finding it would likely violate HB 3115. So the Mayor revised the camping ban to be legally in alignment with the state law and in May, the City Council unanimously passed it. But last week, it was thwarted again, this time by the Sheriff.

Q: How?

A: Outreach workers were instructed to assess and score more than 4,000 camps based on a number of criteria: conspicuous drug use or paraphernalia, proximity to schools, reported violence etc. The camps with the highest score were referred to the City’s Street Service Coordination Center, which then decided whether the camp needed more outreach, referral to police, or no further action.

The S.C.C.C. found eight1 of the 4,000+ camps to require a referral to law enforcement. They gave shelter-or-jail ultimatums to all eight. Seven accepted. The eighth, Alasdair MacDonald, familiar to both police officers and outreach workers for being the subject of numerous calls over the last several months for disturbances, messiness, and potential danger (he had large tanks of gas and propane in his encampment), refused. The shelter offered was one of two tiny houses in the Reedway Safe Rest Village, which he declined, telling the police he’d rather go to jail. So police officers arrested him, and took him to jail, but the Sheriff refused to book him. Instead, he was released and is now back at his encampment.

Q: Why did the Sheriff refuse to book him?

A: Per her official statement, she writes, “we need to utilize the corrections system as a place for people who pose a genuine danger to the public, and that does not include individuals whose only offense is living unsheltered… Arresting and booking our way out of the housing crisis is not a constructive solution. Incarceration is a costly, short-term measure that fails to address the complex underlying issues.”

Morrisey O’Donnell also maintains the city did not request to add the camping ordinance to the her office’s booking criteria—which includes only people who have broken state laws, not city ordinances. The Mayor apparently did not know he needed to make that request, and said his staff has met with MCSO staff several times since the camping ban was passed in May, and no one from the sheriff’s office ever mentioned they wouldn’t be booking people who violated the ban into jail.

Q: Why is this such a big deal?

A: It’s impossible to solve a problem without fully identifying and understanding what the problem is. For years, homelessness advocates have insisted that homelessness is a housing problem that can be solved by building more housing and having more shelter. A lack of affordable housing and appealing shelter (tiny houses > congregate shelter beds) is certainly part of the problem, but the case of MacDonald indicates that the solution to houselessness is more complex.

Q: But the solution can’t just be arresting houseless people. Isn’t the Sheriff right—that arresting and booking our way out of the housing crisis is not a constructive solution?

A: She is right that arresting and booking our way of the housing crisis is not a constructive solution. But as I just mentioned, the housing crisis is not exactly the same thing as the houselessness crisis, despite what some experts say.

Q: What’s the right way out of the homelessness crisis, then?

A: People are homeless for different reasons. For those who are circumstantially homeless—they lost their job, they lost their spouse, they’re on a fixed income and can’t afford a rent increase etc.—housing is a sufficient solution. (Also more innovative approaches to housing: home sharing, ADUs, zoning changes etc.)

But for people who have mental health and addiction disorders, the solution is often more layered. Most cities on the West Coast have been following the Housing First model which posits that a person first needs stable housing before they can address their mental health or drug addiction. It’s a sensible argument, and it is true sometimes. But other times, people move into permanent housing and do not access services and/or treatment and a.) overdose and die in the privacy of their own apartment or b.) behave in a way that makes it unsafe or at least very unpleasant for the other residents of the apartment building. (See this piece I wrote about the Musolf Manor or this one in the Willamette Week about the Buri Building, which is heartbreaking.)

This is the big reason why the city has invested in transitional housing, like the tiny houses at Safe Rest Villages or Temporary Alternative Shelter Sites (they’re essentially the same thing—T.A.S.S. sites are just bigger), for which, unsurprisingly, the Mayor also received considerable pushback, this time from the County. The City’s argument for moving people transitional housing, as opposed to permanent housing, first is that some people need to be stabilized and prepared for permanent housing before they can be successful there.

Q: What do you mean “prepared”? How hard is it really to move someone who needs an apartment into an apartment?

A: All apartment buildings, even apartment buildings built and designed to house formerly houseless people, have rules and requirements—a drivers license or other form of identification, an application, a screening with a criminal record check etc. These things are not always fast or easy for formerly houseless people to acquire or pass on the first try. Again, see this piece for more detail.

Q: What else is the City doing to eliminate houselessness besides arresting houseless people?

The camping ban is the focus of this article, but it’s actually a small part of the city’s overall strategy to eliminate unsheltered homelessness. The city currently operates nine sites, with 576 sleeping units, that, between July 2022 and June 2024, served approximately 1,576 people. Cody Bowman, Communications Director for the Mayor, said the city successfully moved 60 people from Clinton Street Triangle into permanent housing in May and June alone. (One of these people did drugs in his new building, and was asked to leave, but according to Bowman, the other 59 are still housed.) In addition, from 2015 to 2023, the City of Portland spent $1.7 billion on affordable housing development and other services (rental assistance to prevent eviction/potential houselessness), including 4,608 new affordable housing units. (What does “affordable housing” actually mean? I wrote a whole piece about this! Read it here.)

But recall that the entity with the most power and influence in how we address houselessness is the county, not the city. Mayor Wheeler has been fighting—and at times, threatening—to have more say in how the county and city’s Joint Office of Homeless Services spends its budget, because even though the name “Joint Office” implies parity in decision-making, it is the county that is effectively in charge of the office and its massive, $277 million-dollar-per-year budget. Despite tension over this, the city and county did finally agree on a joint plan this spring to add 1,000 more shelter beds, hundreds more more behavioral health beds, and a drop-off sobering center, among other things, which you can read about here.

Q: What is the best argument against camping bans, shelter-or-jail ultimatums, and arrests?

A: Hannah Wallace, founder of the Sunnyside Shower Project (and a Portland Stack subscriber!) makes the argument that the city should first focus on the low-hanging fruit—the many people who want to move into tiny houses in Safe Rest Villages and haven’t been able to get in yet. (She estimates that more than 95% of the Shower Projects’ regulars would move into a tiny house if offered one.) As more people leave the streets and move into SRVs, she thinks it’ll be normalized to the point people like Macdonald will eventually follow suit.

There’s also the fear that incarcerating someone will just lead to more trauma and more neglect, which often makes it even harder to break the cycle of homelessness and addiction.

Q: What about District 3 City Council Candidate Angelita Morillo’s argument, that “people are not service resistant—the services are harmful. The amount of theft, physical and sexual violence, spread of scabies, lack of accessibility for disabled people, all make shelters a scary place to be”?

A: I’m confused about this argument because in her reel, Morillo seems to advocate for services, saying that “it costs more to house people in jail than it does to actually give them supportive services” (i.e. we should be giving them services instead of sending them to jail), but then in a comment on the same post, she writes “services are harmful” and shelters are “a scary place to be.” I asked her campaign manager, Evelyn Kocher, to clarify and also substantiate the allegations Morillo makes against the city’s shelters. “These reports are mainly anecdotal,” she wrote in an email. “However, there have been documented cases of shelters not allowing people in if they do not display a level of hygiene that is extremely difficult to access on the streets, requiring long waits to access beds, laundry facilities, hygiene facilities, meals, or clothing, and shelter staff using their positions of power to sexually abuse shelter residents.” (The claims made by the shelter resident, Hannah Bates, were “investigated, including a review of surveillance camera video, but were not substantiated,” according to Kirkpatrick Tyler, chief of community and government affairs for Urban Alchemy, the non-profit that runs the City’s shelter site, Clinton Triangle.) But then Kocher added that Portland needs “more facilities with wraparound services.”

I also asked Bryan Aptekar, Communications and Community Engagement Supervisor for the city’s program, Streets to Stability, to comment. “It’s [not] clear which locations, type of shelters, programs, or services Ms. Morillo is speaking about. To my knowledge she has never reached out to anyone in our program to understand the nine shelters managed under the City's Shelter Services program. It's impossible to respond to an 'accusation' without any specifics—where, what, who, when.”

Morillo’s reel was made in response to Macdonald’s arrest after he refused a tiny house at Reedway Safe Rest Village and Aptekar confirmed there have been no reported outbreaks of scabies at Reedway “or any of our shelters.” He posited there likely have been incidents of theft and violence, but that “these behaviors are not tolerated in our villages and are considered violations of community guidelines. Police are called when necessary. Our shelters are staffed 24/7, and staff are there to support guests, ensure their mental and physical safety, and address issues if they arise.”

I’ll only add that I’ve met many houseless people who prefer to sleep in their own tent than in a congregate shelter for some of the reasons Morillo notes and some she doesn’t: they’re still active in their addiction and shelters don’t allow drug use, they carry a machete and shelters don’t allow weapons, they like to can at night and shelters have curfews etc. (It’s also true that several of the things she mentions—sexual assault, scabies, theft etc.—are even more pervasive in encampments, but sometimes the familiar wins simply for being familiar.)

Finally, most of the city’s sleeping units are tiny houses, not beds in congregate shelters—which, as Aptekar notes, “were designed, in part, to address and defend against the very concerns raised.” People can lock their belongings in their tiny house to prevent theft and unauthorized entry, there are service providers on site who monitor who enters and exits, and there are a number of tiny houses that are ADA compliant—in fact, according to Bowman, in the Mayor’s office, MacDonald was actually offered one ADA-compliant tiny house and one regular tiny house at Reedway Safe Rest Village, both of which he turned down.

Q: Is this resistance unique to Portland or are other cities experiencing the same thing?

A: It is not unique to Portland; see this piece about Mayor London Breed’s very similar struggle in San Francisco. If we were to have included her and her fight in our illustration above, we could have depicted resistance from the same Ninth Circuit rulings, San Francisco Board of Supervisors president Aaron Peskin, and activists who offer to store houseless people’s belongings in U-Hauls when their encampments are getting cleared, so they can set up new encampments nearby as soon as the city crews leave.

Q: Anything else?

A: Yes, a woman who identified herself as Mr. Macdonald’s sister commented on Morillo’s post and provided some very useful context. She wrote, “The jail is not safer for him, he has been in jail multiple times and it does not solve anything. He has multiple traumas and mental health issues, and needs long-term mental health care—which is non-existent in Oregon unless you are rich… Our family has tried our best for him to not be out there.” I wrote to Ms. Macdonald and asked if, hypothetically, her family was wealthy enough to afford any level of mental health care for any length of time, does she think her brother would accept it? I haven’t heard back yet, but if the answer is no, then we’re back to the original dilemma: What should the city do if it offers services and shelter to someone who clearly needs it and they say no?

Any questions I didn’t answer? Let me know!

Cody Bowman, Communications Director for Ted Wheeler, said there were either seven or eight camps that were referred to law enforcement. To be conservative, I stuck with eight.

Such a helpful, clear breakdown! My brain grew 3 sizes today. It really helped me make sense of what feels like a houselessness holding pattern.

Always so grateful for your crystal clear reporting– helps me understand the nuance of issues like these and makes me feel much better informed!