Goldicops

Was the police response to the Community Free Store and its associated conflicts too much, too little, or just right?

Many years ago, Austrian economists Ernest Fehr & Simon Gächter designed an experiment that sought to solve the puzzle of human cooperation. They wanted to know why humans, unlike other creatures, are willing to cooperate with one another, often in large groups, even when they’re not related or their reputation has little or nothing to gain from doing so. People participating in the experiment were given money and then asked to contribute some portion of that money to a common pot. At the end of each round, the researchers doubled the amount of money in the pot and then distributed it equally among all the participants. In the beginning, people were reasonably cooperative: they gave about half their money to the common pot. But then suspicion set in and they started feeling like they were giving more than everyone else, and so they stopped cooperating—until there was an opportunity for what the researchers called “altruistic punishment” which meant people could use some portion of their own money to punish those who weren’t contributing. Suddenly, people started cooperating again, more and more every round. The conclusion the researchers reached is, “cooperation flourishes if altruistic punishment is possible, and breaks down if it is ruled out.”

Punishment is a terribly unpopular concept in Portland at least in so far as it affects the person being punished (this person needs help and resources, not punishment which will just cause more trauma and more criminal behavior, the argument goes), but this particular study is not about what happens to the individual if he or she is punished. It is about what happens to society, as a whole, if the individual is not.

This should hardly surprise anyone living in Portland, where the persistent level of public disorder has led at least some portion of people here to question their own compliance—why should I pay a parking ticket for staying 15 minutes past my meter when the RV down the street has been parked there for six months?—if not abort it entirely. Nowhere is the disorder more obvious than in Old Town, where it’s not uncommon to see someone start a fire in the middle of the street or walk into traffic not wearing pants or smoke fentanyl absolutely anywhere. There are police officers, but what can they do? An officer once gave a man a ticket for possession and as an indication of how serious the man took the ticket to be, he rolled it up and smoked it. The people here who do follow laws have long felt that the city has abandoned them, that they’re the only ones left in the experiment. It has created, some of them say, two classes of citizens, “where all rules are enforced for the civil, and rules do not apply if you are uncivilized.” The tension, between these two classes, and also between these classes and law enforcement, has been seething for some time, and finally blew up into a bit of a fight last month.

THE COMMUNITY FREE STORE distributes food, clothing, camping supplies, needles, and, together with the People’s Free Library, zines on anarchy, wheat pasting, and primitive toothcare. Volunteers (also called comrades) do so in masks and sunglasses, and almost all of them wear keffiyehs. Of course they don’t show their faces or share their names with members of the media, but this anonymity appears to extend to some of the houseless people who come to the Free Store as well. “What’s your name?” a 30-year-old tribal member from Warm Springs—who did share his name (George)—asked one of the volunteers on a recent Thursday. And the volunteer, from behind his mask, replied, “Who knows?”1

The Free Store is not the only organization that distributes clothing, food, and hygiene items to houseless people in Old Town (far from it), but they appear to be the only one that refuses to get a permit to do so in the street or sidewalk and/or permission to set up in a private parking lot. “We don’t need the city or anyone else to sanction our ability to care for each other,” they often write on Instagram.

None of the neighbors disagree with this, but they do agree that the Free Store needs the city to sanction their ability to close streets, sidewalks, and parking lots and they do want the Free Store to clean up their trash, be kind to the elderly people who live in the neighborhood, not obstruct access to Lan Su Gardens, not block volunteers at the Blanchet House from leaving at the end of their shift, and not set up tents in the middle of NW Flanders, so that cars, ambulances, and firetrucks can still get through if they need to.

Predictably, when residents raised these concerns, it did not go well: “Go home you fucking nimby asshole,” said one Free Store volunteer to a man who asked, last fall, if the Free Store had a permit to be in the street. (This was an odd response, some residents thought, as the man lives in the neighborhood and was essentially home, unlike most of the Free Store members who do not.) Law enforcement tried to talk to volunteers with the Free Store as well and they did not respond to verbal direction (“fuck off,” one volunteer allegedly told an officer in January), so police officers arrived on March 6th with more force. Initially, there were just four officers, but a Free Store volunteer said something to one of the female officers that changed the dynamic: he said the names of her children and the name of their school (it’s not clear how he’d obtained this information) and then, according to the police report, that, “it would be a shame if something happened [to them].” At this point, more officers were called for backup.

Suddenly, several officers were on the scene—witnesses counted 20—citing three people in all, including Alissa Azar, a movement journalist familiar to law enforcement for, among other things, her role in a volatile clash with the Proud Boys in 2021 for which she was convicted of felony riot and second-degree disorderly conduct. (Azar was also arrested last May while recording video at a pro-Palestinian protest at Portland State, although the charges were later dismissed.) On the night in question, police officers cited Azar for crossing outside of a designated crosswalk, a violation many Free Store volunteers found so trivial as to be nothing more than a cover for police intimidation.2

The next week, officers were dispatched to the Free Store again, but this time only to observe and they brought with them representatives of both the city’s and county’s attorneys’ offices because, according to Portland Police Association president Aaron Schmautz, “We wanted to make sure to get this right—we didn’t want it to get sideways.” Such desire might have stemmed from internal reflection or it might have come as a response to a video Councilor Angelita Morillo posted on Instagram titled “How is our police budget being used?” in which she suggests that the number of officers at the Free Store (possibly 20), Councilor Sameer Kanal’s town hall on March 2nd (five), and her event at Montavilla Church on March 6th (two) was potentially excessive and wasteful of resources.

Friends of the Free Store echoed these sentiments in the captions and comment sections of a number of posts that proliferated on the matter, grumbling that Portland police officers have nothing better to do than “harass and assault the houseless community” and those “who dare to help them.” Some Old Town residents found this argument unreasonable, if not absurd. The Blanchet House, which serves hot meals to houseless people three times per day, six days per week, often has a long line of people outside waiting to eat, and police officers have not, in anyone’s recent memory, cited it. Nor have police cited Union Gospel Mission, CityTeam Portland or the Portland Rescue Mission—all organizations that provide services (food, showers, free legal services) to houseless people. Is the difference really just the permit? And if it is, why won’t the Community Free Store just get one?

The Free Store declined to comment, writing, “All the information we wish to share is on our public Instagram account.” Their account is very informative. They write of their disenchantment with many things—the police, non-profits, businesses, capitalism itself—and their desire to extract themselves from those “systems” while trying to build, on whatever scale possible, the world they’d prefer. This is what the Free Store is to its members: a small example of the way things could be, where people who have more than they need share whatever they can so everyone gets their basic needs met and, together, they collectively liberate themselves from the government, the free market, and the mental health industrial complex.3 Much of this writing appears in darling, cursive font, adorned with glitter and roses and rainbows; meanwhile the tone of the text could be described as belligerent, militant, revolutionary. “Just in case we haven’t been super clear what we stand for,” they write, “FUCK THE STATE and FUCK THESE OPPRESSIVE SYSTEMS.” The Free Store will probably never get a permit, because to do so would be to legitimize the state, when in fact their goal is to dismantle it.

This makes relationships with city councilors, even the ones who profess support for the Free Store, somewhat strained. After two consecutive weeks of a police presence at their distribution, Councilor Mitch Green asked Commander Brian Hughes if he’d refrain from sending officers for one week so that Green could go instead and Hughes agreed. Green intended to ask Free Store volunteers how he could “help them run this operation without repeating the conflict,” but he didn’t get that far—they declined to speak with him, requesting that he communicate through their Instagram account instead. They did not seem impacted in the least by his offer (or attempted offer) of assistance at all—the next day, the Free Store posted about the night before: “The city insists on making it hard for us!” (For Green’s part, he blames his approach: “The way I approached them was not conducive to establishing the trust needed to engage in dialogue. I just walked up and introduced myself and some of the organizers were not comfortable with that.”)

Meanwhile, friends and fans of the Free Store identified a new foe to whom they could direct at least some of their anger and frustration—not the police, but someone said to be in league with the police (“cop adjacent”), which seemed to them in some ways worse.

“JESSIE BURKE, the owner of the Society Hotel and Chair of the Old Town Community Association,” wrote From the River PDX on Instagram, “likes calling the police on community members trying to participate in mutual aid and community care." They also took issue with her role as the campaign manager for District Attorney Nathan Vasquez and, as others soon noted, the support she expressed for Israel in a post she’d written in October of 2023. The point of the protest, From the River PDX wrote, was to “Resist Repression from PDX to Palestine.”

The protest was well-publicized and so in preparation (and defense), several of Burke’s friends and supporters filled the lobby—Max Steele, Tiana Tozer, Andy Chandler, and Vadim Mozyrsky, among others—as Burke herself was out of town, on a trip to see colleges with her daughter. The protestors arrived, masked and mostly in black, at 5:30p.m., just as the poster had invited them to. They banged on the windows and doors, which were locked (the hotel began locking its doors in 2020 after multiple of incidents involving, “men with their pants down, people doing fentanyl in the bathroom,” said staff) and this continued for a while until a guest had to open the door to leave and protestors rushed in, shoving the front desk woman, who was eight months pregnant, and punching two of the hotel’s security guards, who were knocked to the floor. (The guards did not have to be hospitalized, but did sustain minor injuries, abrasions and bruises, according to Alex Stone, principal of Echelon Protective Services. Stone says that after his company investigated radical anti-government groups linked with Antifa, Antifa burglarized his office and threatened his life. He and his wife left Portland, and now live in an undisclosed location in the Pacific Northwest.)

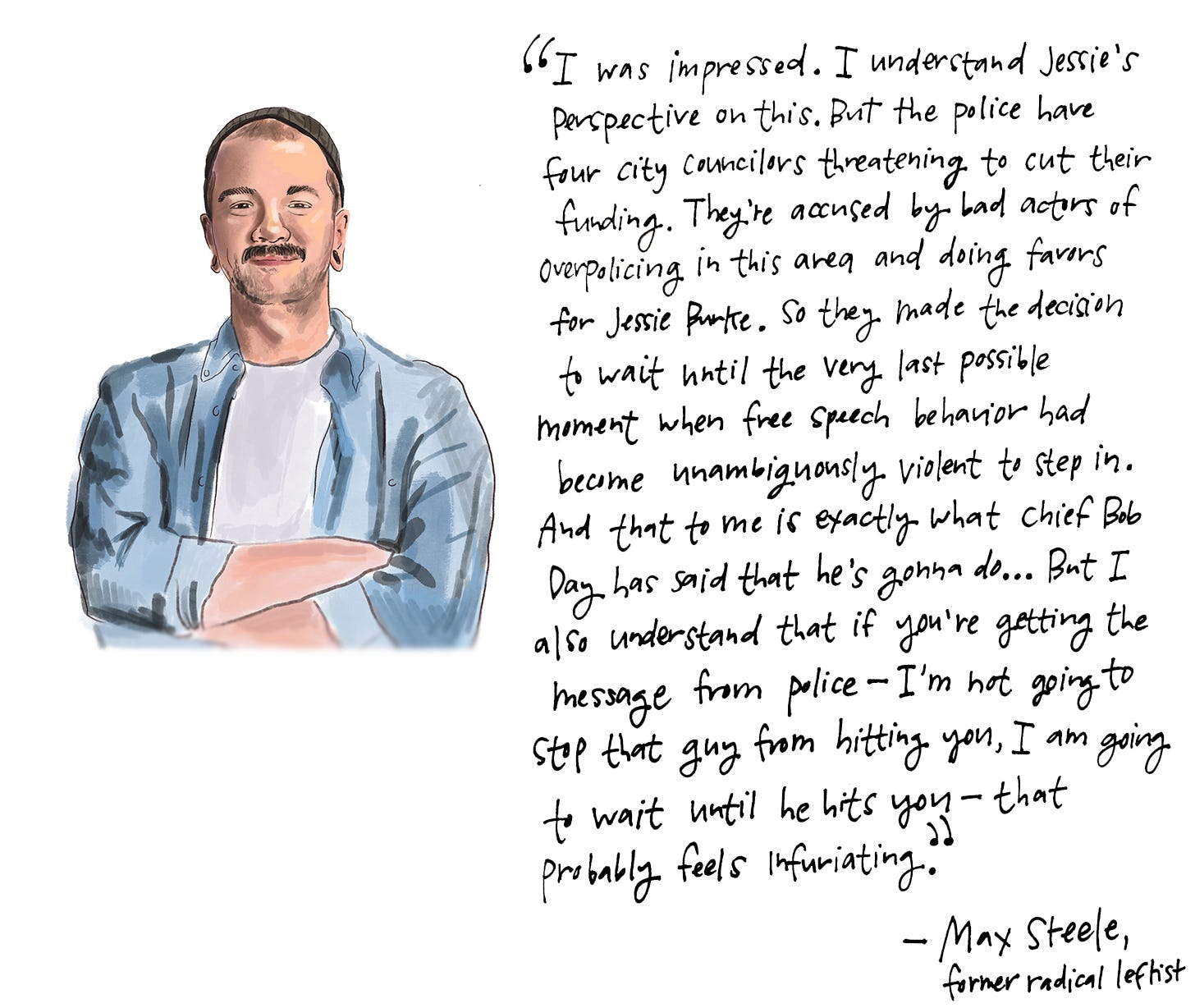

At this point, police officers, who had been nearby, monitoring the situation and watching, as Steele says, “first amendment actions get very, very blurry,” entered the fray and made two arrests: Nicole Middleton, 42, and Rhythm Kenaley, 30. Middleton was charged with Assault III, Attempted Assault III, Coercion, Criminal Trespass, Harassment and Disorderly Conduct and Kenaley was charged with Criminal Mischief.

After her arrest, Middleton claimed in a video that she was arrested for “standing on the sidewalk,” but besides this, the Free Store and its fans remained noticeably silent online regarding both the protest and the police response to it. This time, the criticism came from the other direction—from Burke, who felt that that city and police did too little.

Since the night of the protest, Burke’s car has been broken into twice at her home, her garage has had two attempted break-ins, and someone stole the security camera off her front porch in the middle of the night. “This group doesn’t know anyone in this community—they are guests here,” Burke says. “They show up, scream hateful rhetoric if you ask questions, and then actively spread disinformation while terrorizing the community when they leave (like coming to my house) and then claim they are the victims.”

Meanwhile, the perspective of the Free Store’s fans was that law enforcement actually did too much for Burke (not specifically the night of the protest, but over the course of the months-long conflict). Morillo asked Portland Police Chief Bob Day if “a resident in Old Town privately contacted officers to show up… because it’s my understanding that members of the District Attorney’s staff showed up who are unrelated to this sort of patrol” and Street Roots has put in a public records request for all text messages between Burke and Vasquez.4 (Burke’s reply: “I never once spoke to Nathan [Vasquez] about this.”)

Compliments for police officers are exceedingly rare in Portland, but there was at least one person present at the Society Hotel the night of the protest who thinks the police got it right, and was willing to go on the record to say so.

For the Free Store’s part, it denied any part in the protest, telling the Willamette Week, “it was obviously planned by other groups entirely.” But membership in anarchist collectives like the Free Store is loose by design, and it’s almost impossible to determine where one ends and another begins.5 It’s clear they are, at least on some level affiliated—the Free Store liked Middleton’s post in which she wrote “they’re trying to make me an ‘example’ by hitting me with felonies” regarding her involvement in the protest at the Society Hotel and commented “we’re SO grateful for you all❤❤❤ they will NOT stop us” on Azar’s post from March 7th. Most notably, the Free Store posted on the night of the protest, “another beautiful Thursday Community Free Store” and did not mention, nor condemn, the alleged assault of the hotel workers, carried out, at least in part, in its name.

In early April, the Free Store moved to North Park Blocks, where (predictably) Portland Park Rangers told the group they needed a permit. So they returned to their original spot a couple of weeks later and were last spotted on NW Flanders. They still do not have a permit, and Burke still does not have any assurance that the city will consistently enforce the law, for both the “civilized” and “uncivilized,” the ones still hanging on in the experiment, and the ones who insist on making their own experiment in the middle of the other one. As for what happens if the city doesn’t enforce the law? “Then we don’t have a city,” Burke said. Which is exactly what the Free Store seems to want.

Thank you for reading! I’d love to know what you think.

It’s possible the volunteer didn’t give his name to George because I was listening. I wish I could ask them, but they declined to comment or answer any of my questions.

I asked the Portland Police’s Public Information Officer, Mike Benner, about this specific citation, and he replied, “We are not going to begin dissecting pieces of video on social media,” and that all the information I need should be in the police report.

I also relied on the personal accounts of Free Store members after I was blocked from from the main account, especially this one, as she is one of CFS’s earliest members.

I wanted to ask Morillo if, after the violence that occurred at the hotel, she saw law enforcement’s presence at the Free Store differently, but she did not reply to my requests for comment. I sent her two emails and left two phone messages.

I asked the Free Store what its relationship was with Middleton or Kenaley, and they blocked me.

wow this is so complex; I admire your tenacious attempt to clarify and explore this issue! Without living in Portland and understanding the issue(s) firsthand, it feels like a microcosm of the larger social conflict(s) we're facing everywhere.

The real question: who's paying for these masked thugs? The history of the radical movement in recent history is liberally salted with FBI/intel agents who seem to appear and disappear at random. Some are arrested--good show for the comrades--and then, poof!, charges disappear. Antifa come; Antifa go. Nonprofits launder "contributions," but no one knows where they come from (the Supreme Court that radicals profess to hate guaranteed the right to keep that little secret).

General rule: if someone says it's so, it ain't.