Let’s begin where we left off: We now know how to get people who want to go to treatment into treatment. Importantly, it is not a hotline, which we tried under Measure 110, and it failed very badly. No, the way to get people who want to go to treatment into treatment, as illustrated in the previous story about the pilot program between police officers and outreach workers (that recently got funding to expand!), is to find these people wherever they are and immediately connect them to a peer support specialist who’s in recovery, who knows where there’s an available spot (at an out-patient program) or bed (at an in-patient program), and who can take them there or arrange for someone else who can.

But only one in five people police officers and outreach workers encounter are interested in treatment. The much harder question is what to do about the other four in five drug users who resist or refuse treatment.

All spring, a debate raged in Oregon about this very question as lawmakers debated bills that would back criminal penalties, or at least the threat of criminal penalties, for drug possession. The legislators who supported these bills, including the one that would eventually pass, House Bill 4002, answer the question above like this: if drug users refuse treatment, tell them jail is the only alternative. Those opposed argued the bill constituted a return or reinstatement of the drug war in Oregon. Thousands of people weighed in, panicked about this very outcome, but it becomes clear upon reading their testimonies and comments that a great number of these people are quite confused about what a “return” in Oregon would actually mean.

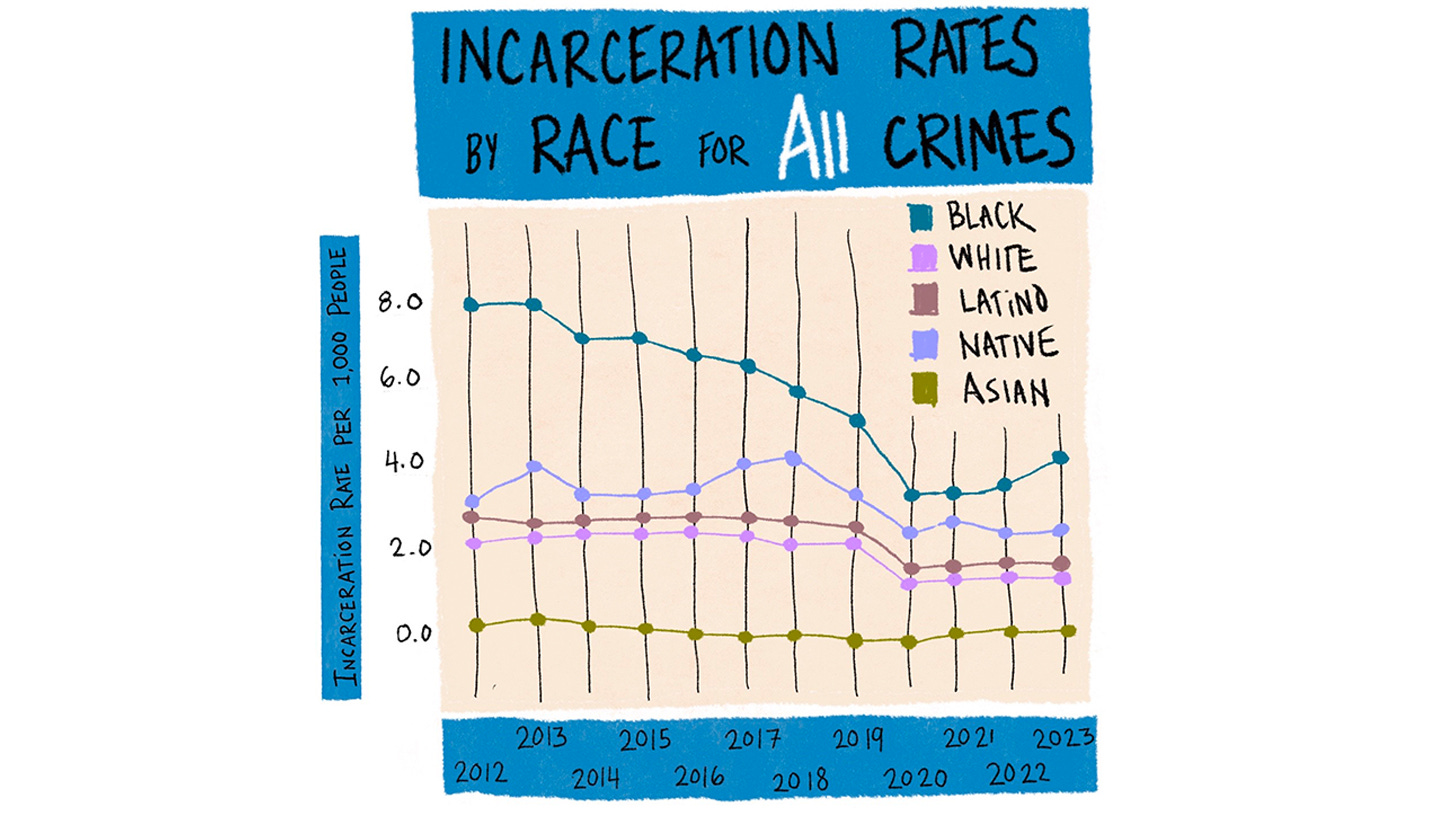

Consider that in 2020, at the time Measure 110 passed, there was not a single person in prison in Oregon solely for possession of a controlled substance. In fact, the state had not sent anyone to prison solely for possession in roughly 40 years. In 2016, then governor Kate Brown commissioned a first-of-its-kind study in Oregon to look at racial and ethnic disparity in the state’s criminal justice system, and when the study did find that disparities existed, state lawmakers passed a rather big bill the next year to address them. The bill downgraded possession of a controlled substance from a felony to a misdemeanor, required police officers to collect demographic data in traffic stops, and ordered the state’s criminal justice commission to analyze that data, as well as the composition of convicted offenders and rates of recidivism. This law was only in place three years before Measure 110 supplanted it, so the data is very limited, but here is what it is:

These graphs do not tell a perfect story, for perfect would mean no disparities at all. But neither do they make the case that we are set to return, in Oregon, to the horror that was the war on drugs as it was originally conceived by Nixon and his advisors. By almost any metric, the situation was improving here. Incarceration rates were down. Arrest rates were down. Felony convictions for possession were down (obviously), but even with the corresponding increase in misdemeanors, overall convictions (for felonies and misdemeanors combined) were down. Racial disparities in incarceration rates for all crimes, including drug crimes, were shrinking.

But these data points rarely figured into the conversation, either because they did not sufficiently impress the critics, many of whom saw anything less than the full decriminalization of drugs as pointless, or because the slow, incremental changes that were happening here undermined the idea that we needed a big, disruptive measure like Measure 110 in the first place.

There was something else that seemed to be missing (if not misleading) in the critics’ case against the bill to bring back criminal penalties as well, and that is that the legislators who wrote the bill were (are) not really trying to get drug users to go to prison. What they were trying to do is use the threat of prison to get them to go to treatment. Here we get to what was often missing, or at least what I thought was missing, in the argument for the reinstatement of criminal penalties for possession, which is: does this work? Can you really compel someone to go to drug treatment who doesn’t want to and expect them to recover?

I interviewed so many people, and read so many studies and articles about this, and gathered what I think are the best arguments, for and against, and present them to you here.1

One question might be: Why even have this debate? Didn’t Sam’s side definitively win the day the governor signed the bill into law, empowering police officers to arrest people in possession of illicit drugs and offer them either treatment or jail?

Not definitively, no. The new law gives enormous authority to individual counties and tribal governments to decide 1) if they want to have a pre-booking deflection program at all2 and 2) what the consequences will be if a person does not want to be deflected into treatment. In Multnomah County, for example, people found with street drugs will have a choice: get arrested or get taken to a drop-off center where they’ll be required to undergo a screening and get referred to services, but not necessarily enroll in those services. They can leave the drop-off center as soon as the screening process is over with no further penalty. (If this sounds futile, consider that in the first iteration of the plan, the County was not even going to require a screening.) Evidently, the architect of this approach, County Chair Jessica Vega Pederson, comes down closer to Joe’s side in the debate, and in terms of how the law will work in Portland, hers is the final word.

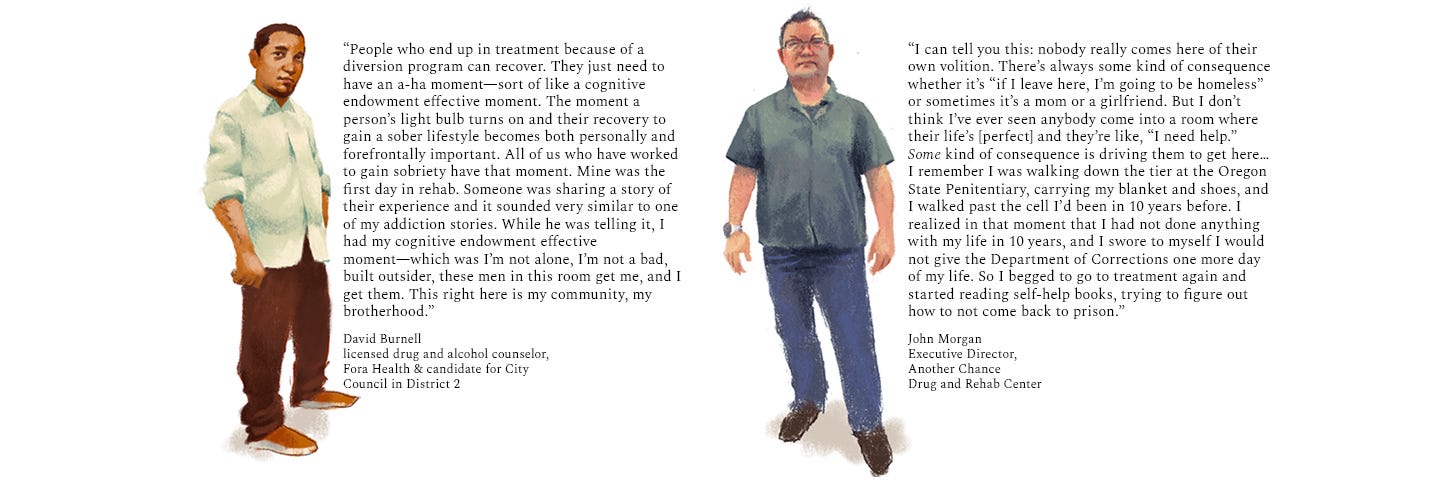

But even if politically the issue remains fraught, the research is actually fairly consistent. The largest study on the matter, which examined the outcomes of 2,095 people, found that mandated patients did as well or better than voluntary patients in their ability to stop substance abuse, procure employment, and avoid arrest. Another widely cited study which randomly assigned 235 people either to drug court or “treatment as usual” found that people who went through drug court were almost three times as likely to receive treatment for their addiction. Most people I spoke with for this story—people who are both in recovery and who now work with others trying to get into recovery—said something of similar effect, in line with the findings of these studies.

So it is possible to send a person to treatment and for this person to recover, even if the only reason he agreed to go is because prison was the only alternative.3 But it is not guaranteed. No one should be so naive as to assume that getting a person to go to treatment is the same as getting this person to succeed, or even stay, in treatment. Here is one woman, only 28 years old, who has already been in and out of treatment approximately six times, but she’s not sure, because she’s lost count:

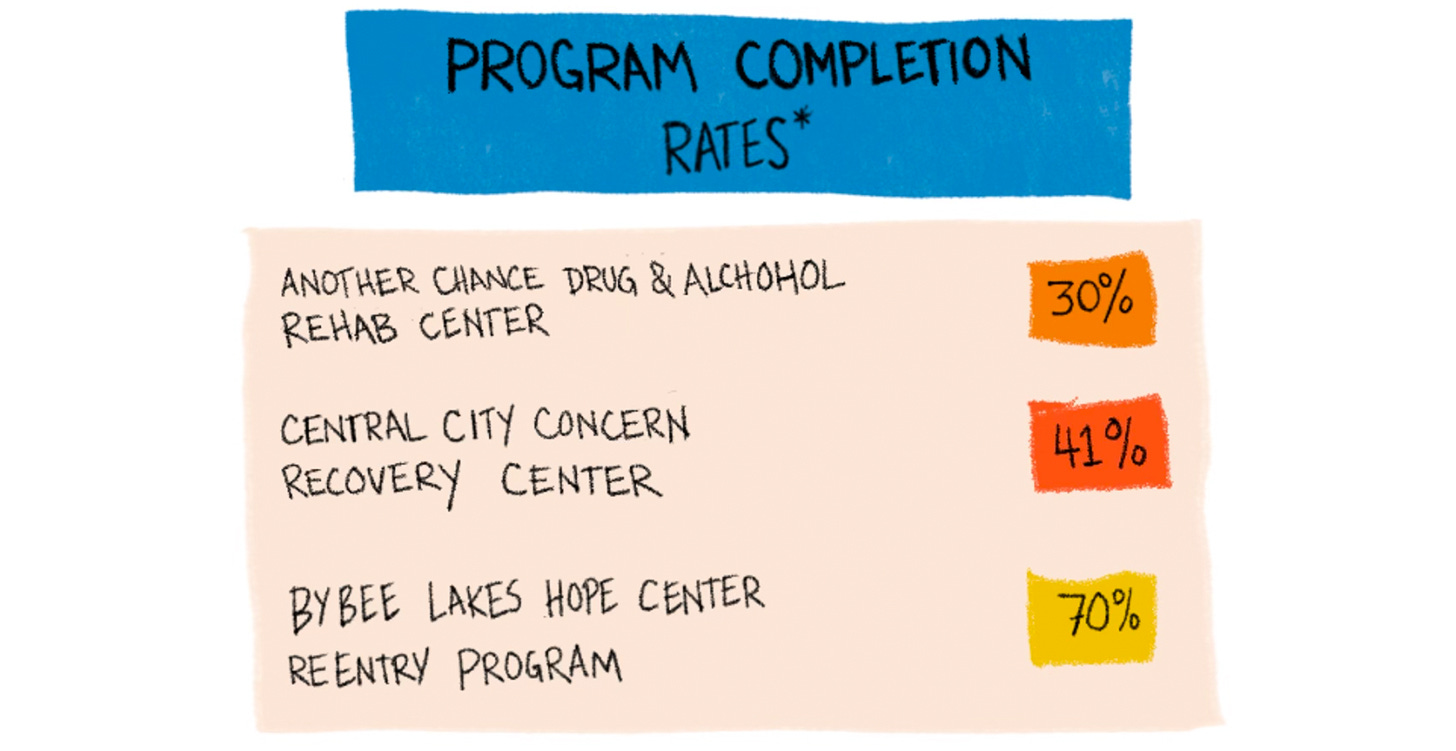

Danielle’s is a typical recovery story, except that in the end, she recovers. That is somewhat rare. But going to treatment and leaving to use again is very common, and belies a much bigger issue in our current, collective crisis, which is that the rates of completion for people who go to treatment, whether they are compelled to or not, are actually very low. And “program complete” does not necessarily mean clean and sober. In fact, it means something entirely different in each program. Keeping this in mind, here are some completion rates in Portland:

This, I think, is the real issue—what the focus of the conversation should actually be if we’re serious about ever getting out of the addiction crisis in Portland. It’s not if the new law in Oregon is a return to the war on drugs (it isn’t), and it’s not if you can successfully compel a person to seek treatment even if the person is not “ready” (you can), but rather: What is the most effective kind of treatment? And are we doing it? Coming soon! How soon? The more support I have, the more I can focus on reporting, and the faster I can finish.

A short preview: There is one intervention that has proven to be quite successful, possibly more successful than any other in helping addicts achieve abstinence. When I asked the County’s health department if it funded any programs that employ this strategy, the answer was no. Any guesses on what it might be?!

The writer Morgan Godvin also makes a compelling case against drug criminalization, but the argument in her piece “I Thought Jail Would Help Me Get Clean. I Was Dead Wrong.” centers on the jail’s refusal to give her Suboxone. I did not include this argument above, because the new law (that re-criminalizes possession) also includes $10 million for medication assisted treatment in jails as part of the new Oregon Jail-Based Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Grant Program, so it seems unlikely that patients in the future will be denied Suboxone, as Godvin was.

So far, 23 counties in Oregon, representing 85% of the state’s population, have opted to create deflection programs.

Whether it’s ethical, as Joe says, is another question, although to be fair, there is an equally compelling argument to be made, as Sam does, that failing to intervene when someone is posing a harm to themselves and others, and clearly has compromised reasoning skills as a result of drug use is also unethical.

You're so smart, it's overwhelming.