The Forbidden Poster

The debate we're having here about how to best get people off the streets is the same debate almost everyone is having, everywhere.

Late last September, after a month of meetings in which the Multnomah County Board of Commissioners discussed how to best spend an unexpected $63 million in funding specifically to help end homelessness, Commissioner Sharon Meieran tried to present her own plan to end homelessness that she’d detailed in a flow chart and printed on a poster. But when she pulled out the poster to put it on display, the Chair, Jessica Vega Pederson, blocked her from doing so, telling Meieran it was not the time for displays, only board comments.

“These are my board comments,” Meieran protested. But Vega Pederson didn’t budge, and the contents of the poster remained undisclosed. Predictably, the prohibition of the poster only added to its allure, and soon, Meieran began to receive a flurry of emails from curious constituents asking what was on the forbidden poster?! (To be clear, Vega Pederson did not prohibit the actual poster, but the process in which Meieran attempted to share it. “It was about timing,” a source in Vega Pederson’s office told the Portland Stack. “And procedure.”)

In response to this surge in curiosity, Meieran hosted a virtual town hall in which she presented her plan to eliminate unsheltered homelessness that she called “Connecting the Dots.” She and Vega Pederson support many of the same strategies—better behavioral health services, rental assistance for people at risk of becoming homeless, and supportive housing for people who are currently homeless—so it was not surprising when, in the question and answer session, more than one constituent asked what the differences were between her plan and the Chair’s. In reply, Meieran reiterated what she’s said many times before: Vega Pederson doesn’t have a plan.

Remarkably, a source from Vega Pederson’s office confirmed this. The Chair is convening groups of people to listen to their perspectives and understand what they need, the source said, and, “a plan is forthcoming.”

This both gives context to Meieran’s frustration the night she tried to present her poster—$63 million is a lot of money to spend without an overarching plan, to say nothing of $279 million that is the Joint Office of Homeless Services’s annual budget—and makes it difficult to answer the constituents’ question about the differences between the two commissioners’ plans. But the Portland Stack will still try, because it is a valid and important question, and it’s the job of journalists to inform the electorate about what options there are to get us out of the crisis we’re in. (It’s true that voters already decided between Vega Pederson and Meieran when they ran against each other for County Chair in 2022, and chose Vega Pederson—perhaps solely because of her housing platform, but more likely due to a mix of her plans, temperament, endorsements, and incredibly popular Preschool for All initiative, which despite a slow, somewhat rocky start seems to be finally ramping up. The point of this piece is not to pit the complete candidates together as they are in a political race—only their plans to tackle homelessness.)

In lieu of a comprehensive plan from Vega Pederson, we used one of her smaller, more targeted plans in our comparison below: Housing Multnomah Now, her plan to rapidly house 300 people in Portland’s Central City last year. (It housed 25.) This makes for an imperfect comparison of course—we’re comparing a micro plan to a macro one, an implemented plan with a hypothetical one—but it still illustrates essential differences between the two commissioners’ approaches, not only in terms of their timelines and trajectories in getting people off the street, but also what they think causes homelessness in the first place. When you’re solving for different problems, the solutions are bound to be different as well.

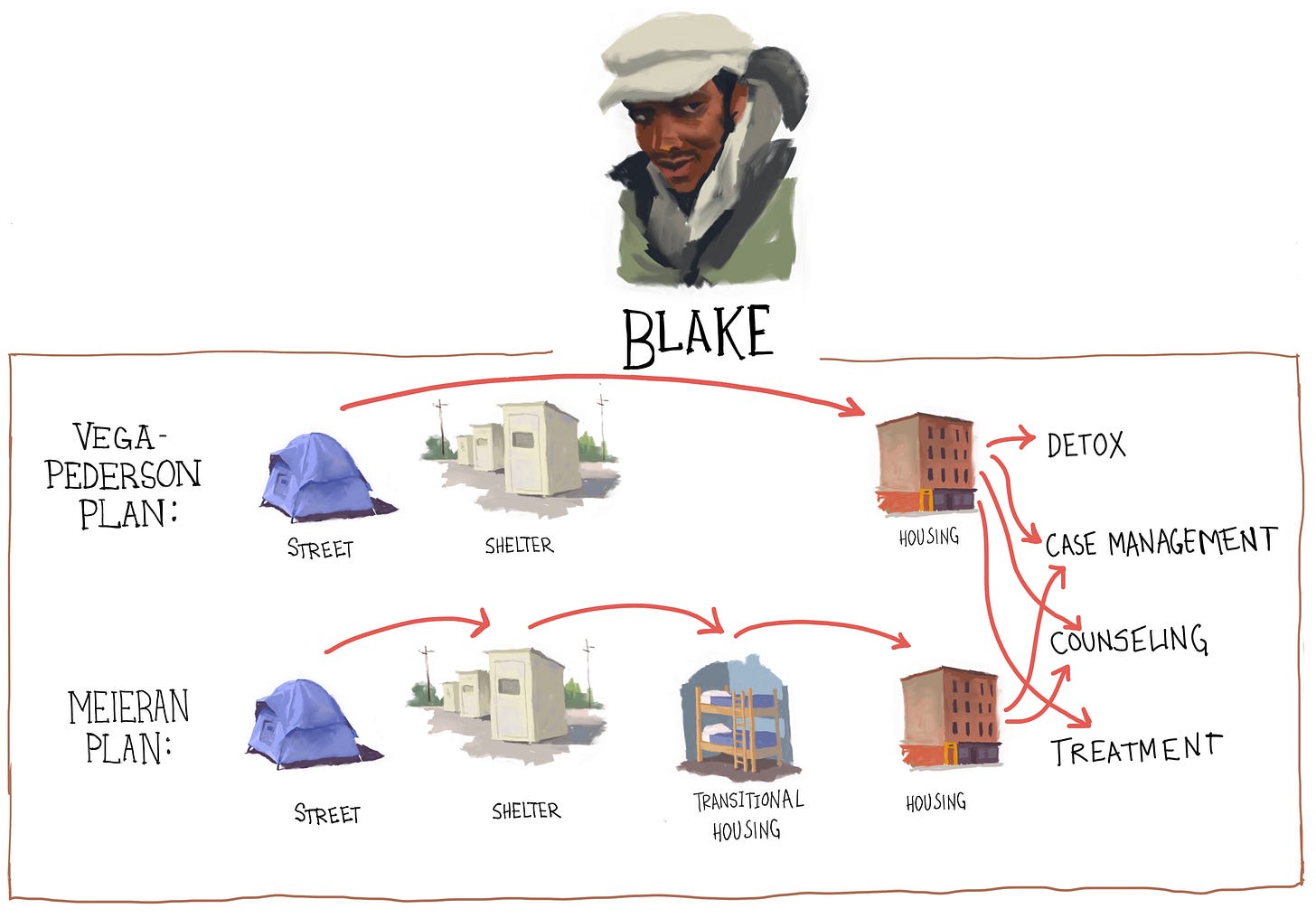

In Vega Pederson’s plan, people who are living on the street or in shelters are to move directly into housing. Once they’re housed, they may access services—detox, treatment, counseling, case management etc.—if they wish to do so.1

In Meieran’s plan, some people who are living on the street would be moved directly into housing, some would go to a shelter first, and some would go into transitional housing, such as the re-entry program at Bybee Lakes or the residential program for drug and alcohol treatment and co-occurring mental health disorders at Fora Health first. Then, these people would move into housing. (There, they’d have access to the same services mentioned above.)

You’d be forgiven if it seems like we’re splitting hairs, making what may seem like a trivial difference—moving all houseless people straight into housing vs moving some houseless people straight into housing and others into transitional housing or treatment first—into the subject of 3,000-word story. But this distinction is actually the stuff of great, even explosive, debate among researchers, reporters, policymakers, and people who work with houseless people everywhere. It is a litmus test for something much larger, and it’s worth understanding why.

Vega Pederson and Meieran both know that homelessness is caused by multiple factors, often overlapping and exacerbating one another, and they agree on what many of these factors are—a lack of affordable housing, not enough shelter beds, and a housing process that’s slow and complicated, practically impenetrable to those who need it most. But plans are about priorities. They are written to solve problems in order of urgency and magnitude, and it’s clear Meieran and Vega Pederson have identified very different problems as the most pressing to solve.

Consider this line from Vega Pederson’s budget2 last year: “Every institutional failure that is driving highly vulnerable people into homelessness is exacerbated for Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC) by the endemic racism that plagues those institutions… systemic racism continues to channel disproportionately high numbers of People of Color into homelessness and create barriers for BIPOC individuals to overcome in ending their homelessness.” Along similar lines, the two factors in homelessness Vega Pederson mentioned last month, while giving remarks at the release of the Domicile Unknown report, were “our complex systems” and racial injustice. In her view, it’s systemic failures, in particular systemic racism, that cause people to become and stay homeless, and that is what needs to be fixed. It follows then that Vega Pederson has made reducing racial disparities in homelessness one of her top priorities. (In Oregon, Black or African American people make up 2.3% of the general population, but 6.9% of the homeless population—although Vega Pederson usually cites the national percentages, presumably for greater effect, with Black or African American people representing 13% of the national population, but 37% of the homeless population.)

Meieran’s views on race do not seem to be so ideologically far from Vega Pederson’s (“I encourage you to research & reflect on the racist history of Oregon & anti-Black systems of oppression that still exist today, AND take action to fight injustice & uplift Black & Afro-Indigenous people & orgs,” she tweeted last year), but rarely does Meieran mention them when discussing homelessness. Instead, Meieran, an emergency room doctor and Portland Street Medicine volunteer, has observed that mental illness and addiction are the “massive contributors” to homelessness, and that is what she has designed her plan to address. Thus, in her plan, transitional housing—meant to provide an intervention for addiction and mental health disorders, and help build the skills necessary to live inside again—is for some people a recommended step before housing, not an optional service afterwards. “Meieran [wants] people to go into housing when they’re stabilized enough to go into housing,” Meieran’s chief of staff, Adam Lyons, said.

This is a risky, controversial position to take in a city like Portland, as it’s often a progressive reflex to want to deflect responsibility away from individual people, especially vulnerable or marginalized people, and find fault with The System instead. The kind of morality behind this, which is pervasive in Portland, is principally organized around the degree to which a person is vulnerable or marginalized: the more vulnerable or marginalized, the more moral status this person (and their allies) have. For people who have these reflexes or follow this moral order, the mere mention of treatment or transitional housing before permanent housing is suspect, because it suggests that houseless people might not just be victims of systemic injustice, but also participants in their own unsheltered circumstances. It asks not just the system to change, but the people who are living outside, especially those addicted to drugs or alcohol, to change as well.

There are, of course, pragmatic—not just ideological—reasons to house people first. “The reason we want people to have housing before they go to detox,” Will Kastning, the supervisor for the Housing Multnomah Now team at Transition Projects said, “is so they can have a place to come back to.” Otherwise, they might end up back on the street. Also, Housing First advocates argue, people need the stability of permanent housing before they can address other issues, like addiction and mental illness.

But there are also good reasons to move some people into residential treatment or transitional housing first: it can be dangerous to put people active in addiction behind closed doors (in Seattle, 179 people who were living in supportive housing died of overdoses in a single year), it’s difficult to maintain and insure public housing units frequently damaged by residents who are not clean or sober, and it’s even more difficult to persuade other houseless or low-income people to move into a building where drug use, and all its attendant problems, are rampant.

As with any policy, it’s tempting to debate it in theoretical terms, but much more useful to see it in practice—in real life, with real people who tend to illuminate and complicate even the best laid plans.

For someone like Marshall, who does not struggle with substance abuse and does not have any mental health disorders, his pathway out of houselessness would look exactly the same in Vega Pederson’s and Meieran’s plan: street to housing, with nothing in between—which is exactly what happened. As we wrote about in our last piece, Marshall moved from his van to the Musolf Manor in early 2023.

Mark, the subject of our first Portland Stack story, miraculously got clean from meth on his own while living on the street, but still struggled with alcoholism, and had (has) several mental health issues: bipolar disorder, attention deficit disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. His case manager wanted to move him directly from the street into housing—exactly what Vega Pederson’s plan would have him do—but couldn’t, because Mark had an open case on his record. (Kastning, at Transition Projects, said legal issues are the single biggest obstacle to getting people housed quickly: some of them have warrants out for their arrest or convictions on their record that need to be resolved before most buildings will allow them to move in.) Mark’s case manager moved him into a motel, thinking he wouldn’t be there long—motels are by far the most expensive way to shelter people, approximately three times as much as transitional housing—but he ended up needing to stay a full five months while a small, but dedicated army of people at Northwest Pilot Project, the Sunnyside Shower Project, the Multnomah County District Attorney’s Office, and, eventually, the Pima County Attorney’s Office in Arizona all worked tirelessly to resolve Mark’s open case. He ended up being denied for something else—a disorderly conduct charge from a time he was drunk and belligerent at a bar, but his case manager and supporters wrote letters on his behalf and successfully appealed the decision in the spring of 2022, and he’s been housed ever since.

I asked Meieran specifically what would have happened to Mark under her plan. She said she would’ve wanted to address the underlying issue—a reasonable response, but not an altogether clear one, because again, it depends on the lens used to decipher the underlying issue. To some, it’s the drinking; to his case manager, it’s our system’s lack of mental health and addiction resources, particularly the ones that accept public health insurance (which are too few).

Also, Mark was not interested in transitional housing that requires sobriety like the one at Bybee Lakes, so it would have been interesting to see what would have happened if he’d had a case manager who was working within Meieran’s plan.

Not long ago, Josette lived in an abandoned house, addicted to IV meth and crack cocaine, while her daughter was in foster care. Josette’s path out of houselessness is more aligned with Meieran’s plan—she first went into rehab, then into sober living, and finally, into housing. We’ll never know what would’ve happened if Josette were to have followed Vega Pederson’s plan, but it’s possible she would have had more culturally specific care, which Vega Pederson has significantly invested in. It would have been interesting to see if that would’ve made a significant difference in Josette’s case. Josette now lives with her daughter in a two-bedroom, tax-credit unit for low-income households and works as a peer support specialist for Northwest Pilot Project. She’s thriving.

Blake is shy and soft-spoken, and likes to dress in a delightful, whimsical way—he wears a white, shearling coat and a pirate’s eye-patch on his forehead, and he likes to carry a red, toy sword. He’s very generous: people are always walking by him, asking him if they can borrow his lighter and he always says yes. Blake is originally from Columbus, Georgia, and although it gives me no pleasure to tell you this, he moved to Portland because it’s easy to survive here. “There’s food there,” he said, pointing to the Blanchet House, and “and food there” (pointing to Union Gospel Mission) “and showers…" somewhere. (I wasn’t sure where he was pointing to exactly.) He’s 30 years old and addicted to meth. It’s difficult to find him to talk with him when he’s not high, which is something outreach workers also struggle with—how to develop trust, rapport, and a relationship with someone who is in a profoundly mind-altered state most of the time—but when I do, he doesn’t seem interested in going to a congregate shelter, although it’s possible he could become interested in going to a shelter that provides more privacy like a Temporary Alternative Shelter Site or a Safe Rest Village as a first step. Maybe if Blake moved there, he’d be easier for outreach workers (and journalists!) to find and develop a relationship with, and maybe, hopefully, having a bed to sleep on and a door to close might give him enough space and stability to take the next step to… recovery-oriented transitional housing or housing (?!), depending on which commissioner you ask.

Mini epilogue: Vega Pederson’s approach seems to have evolved since she first launched Housing Multnomah Now. When Mayor Wheeler initially asked the county to financially contribute to the large sanctioned camps (now called Temporary Alternative Shelter Sites) he wanted to build, Vega Pederson declined—that’s not the model, a source who works with Vega Pederson explained—but later, compromised. (Some of the 25 people who were housed under Housing Multnomah Now first went to one of these shelter sites, after their camp under Steel Bridge was swept.) And after a particularly charged meeting last September, in which a number of recovery advocates gave public testimony, pleading their case for the County to spend more money on drug treatment, Vega Pederson increased the funding she’d originally proposed for behavioral health, crisis stabilization, and recovery housing from $12.9 million to $15.2 million. Her relationship with the County’s biggest transitional housing provider, Bybee Lakes, still appears to be strained though—more about this in an upcoming piece.

Readers, which plan do you think has the best chance of getting us out of this crisis? Or do you have your own plan? Tell us all about it ↓

This was the plan, and, according to Kastning at Transition Projects, 24 of the 25 people who were housed under Housing Multnomah Now followed this trajectory. The one man who didn’t took the unusual path from the street to the Clinton Triangle alternative shelter site to detox then back to Clinton Triangle and then into housing—a regular, market-rate apartment that is paid for with rental assistance from the County. I’m working on getting more details on how he’s doing now—still in recovery? accessing services? working or not working?—and will update the story when I do.

The FY 2023 budget began under the previous Chair, Deborah Kafoury, but was, according to sources in Vega Pederson’s office, very much a collaboration between Kafoury and Vega Pederson, who took over the chairmanship January 1, 2023.

Informative and thorough piece. Glad you're out there painting the whole picture!

Great piece, Devin. I think Meieran sees this as the crisis it is, while JVP is dithering in semantics and it DRIVES ME CRAZY. I also think Meieran is right that we need more flexibility in how we house people. People aren't always ready, like Marshall, to go straight from the street (or van) to housing. [As much as I'm a fan of Housing First. But Housing First usually means housing w/supportive services.] Transitional housing like the SRVs can be an important step before actual housing. (You can get into detox and/or seek better access to mental health care while you are in the SRV--at least that's the idea.)